Home |

Gallery |

Books |

Memories |

Contact |

|---|

Stories from my past

Intermittent thoughts on a variety of subjects, mostly science and art. A journey through my relation to fine art, figurative painting, conceptual art, sculpture, a bit of interior design and some childhood memories.

Feel free to browse or choose from the list of memories below...

|

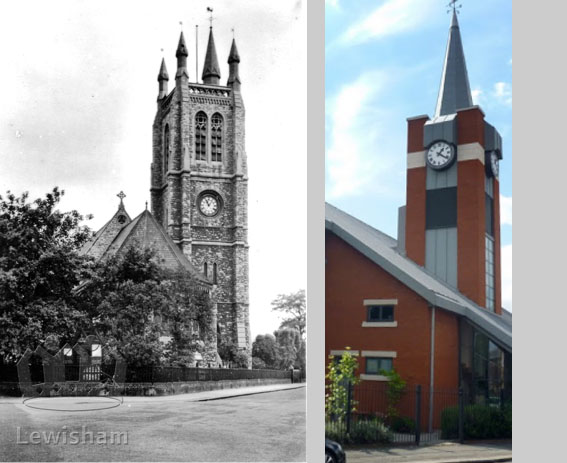

Uncertain at St Dunstan's College

|

|---|

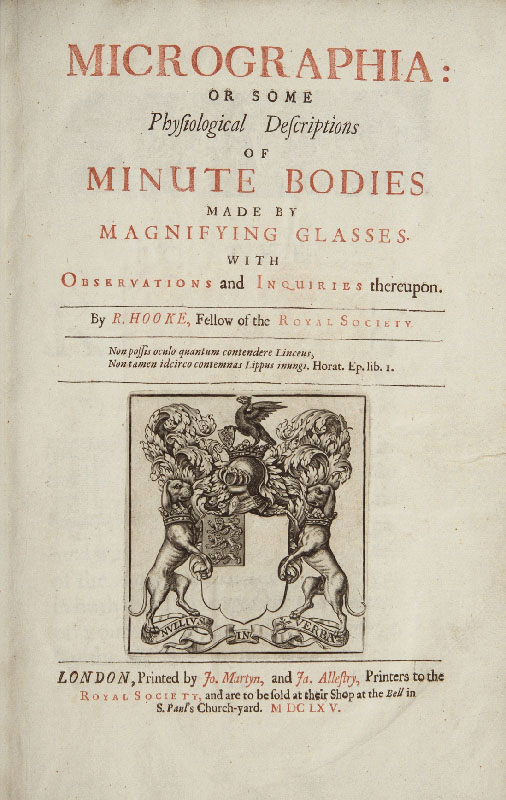

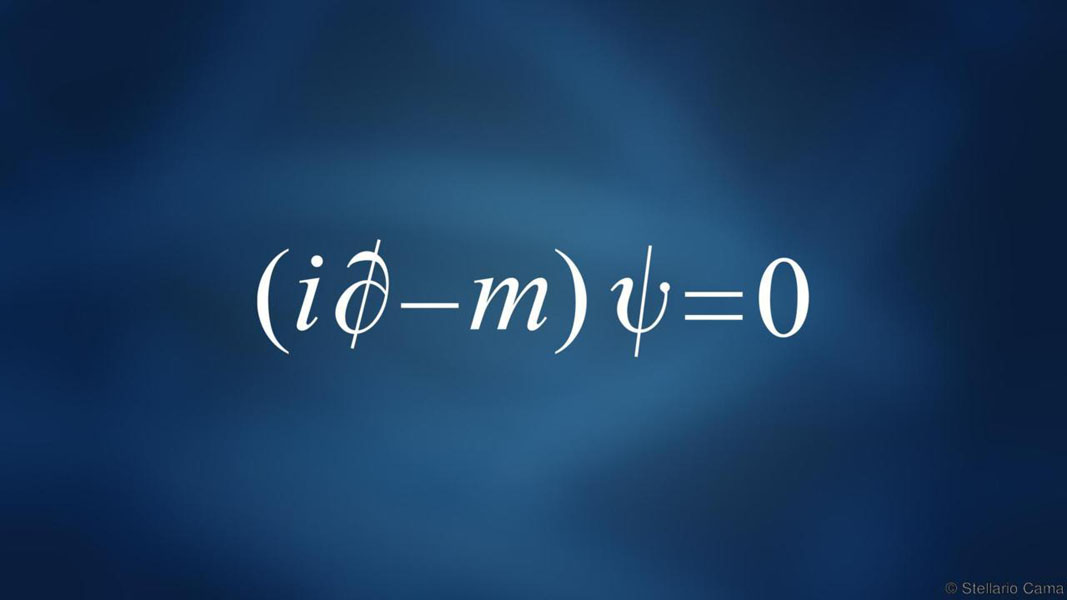

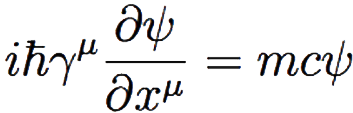

Time's up

On a quest to find things that nudge towards current truths scientists come up with experiments actual or in thought. Listening to a series of lectures The biggest ideas in the Universe (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HI09kat_GeI ) from Sean Carroll, I face an inability to completely grasp our differences. It's a trivial relief from my concentration when he sidesteps from where he wants understanding to be at current rest, into the domestic. Two of these occur when he turns to deal with his cats … "he's a great cat" and another later in the series … "wants me to play with him." By the by I think his two cats are named Ariel and Caliban from The Tempest so perhaps he has an interest in the arts alongside his scientific studies. These minor distractions don't really stop me trying to follow quantum physics; I plough on bewildered but at least catching the odd glimpse.

Alongside his 24 lectures I have listened to Juliet Stevens reading The Golden Bowl by Henry James. Would that I had changed as much as Maggie whose strength and understanding blossom as the pages pass. While Maggie engineers her family into positions, places even, that helped me see errors I had made, Mr Carroll made me think about where that past might be. Linking thoughts between quantum fields and Maggie's plight in the Bowl may seem odd, ridiculous even, but at the very least it makes me think there's more to betrayal than primary reaction.

It's easier to click magnets onto a refrigerator door than to remove them, admittedly only slightly but there is a difference.

It's easier to avoid quantum field theory than try, at the very least, to have a wee peek at what others are doing.

It's easier to begin an understanding of 'fields' once we have recalled those we witnessed with magnets.

It's easier to understand the significance of a/the crack in The Golden Bowl than to imagine one across our Moon.

I look out and upwards at the Moon,

A crack across it.

Two weeks go by, the Moon is split in two.

I study the separate pieces through my telescope

No further cracks appear. Anon.

Besides the difficulty of Field Theory one, and only one, of the many things Mr Carroll and The Golden Bowl bring to mind is time; what a tricky subject …

I remember hearing Samuel Beckett's play Lessness, read on Radio Three back in the 1970s, here's a quote or two

"Old love new love as in the blessed days unhappiness will reign again."

"Figment light never was but grey air timeless no sound."

"Blacked out fallen open four walls over backwards true refuge issueless."

I'd miss-remembered some of his beautifully read but shocking lines from the 1970s radio three programme that over the years have brought tears to mind rather than eyes; making me wish I had tape recorded its reading … To be able to listen again to readers Donal Donnelly, Leonard Fenton, Denys Hawthorne, Patrick Magee, Harold Pinter, Nicol Williamson would be wonderful

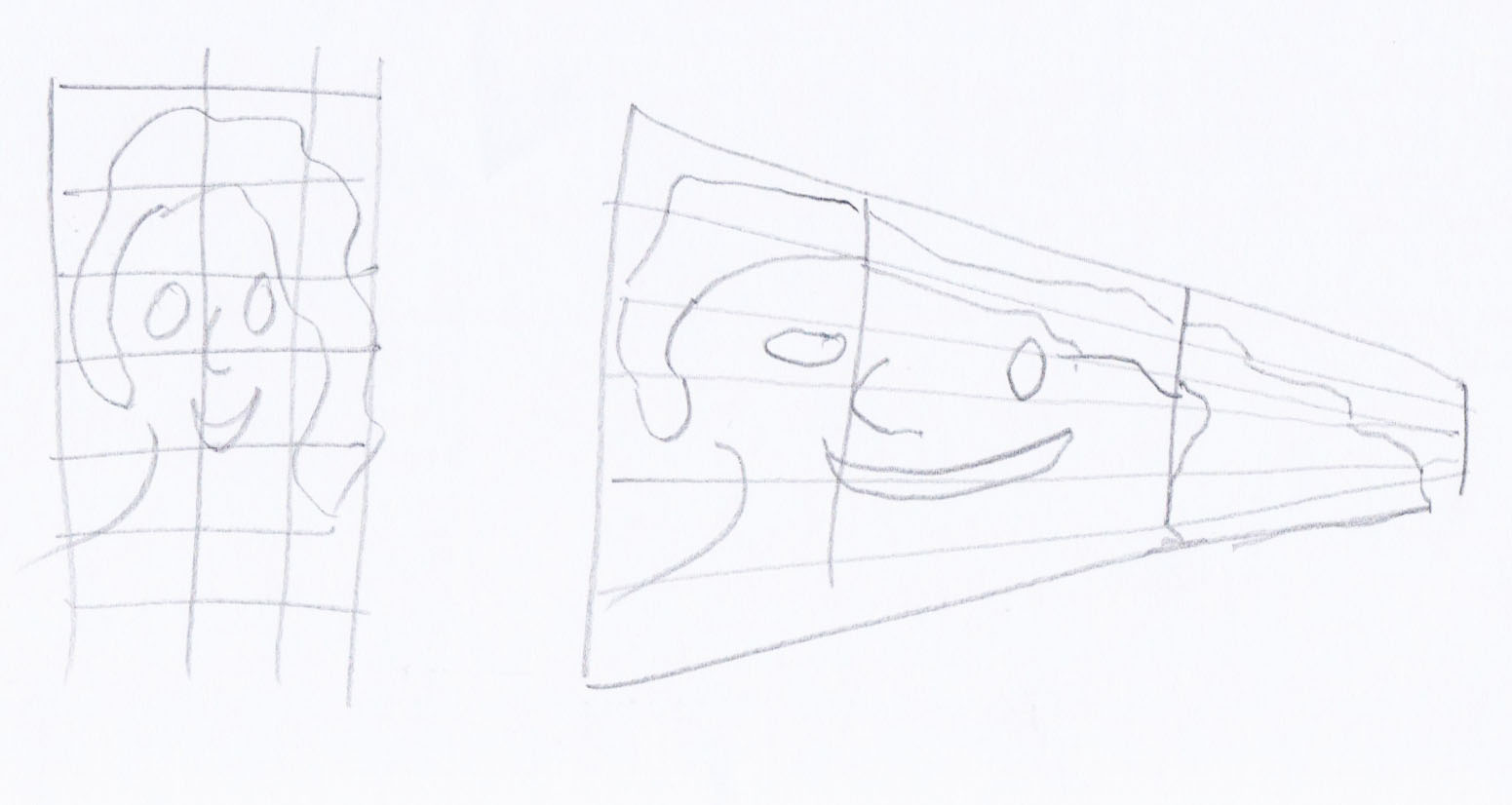

Apparently Mr Beckett wrote all of the sentences for this work on separate sheets of paper and selected the final order at random. There is a view of time as a filmstrip, separate images like that link to movement when passed at speed. What might it be like were the 'time filmstrip notion' projected in a random order rather than a continuous flow?

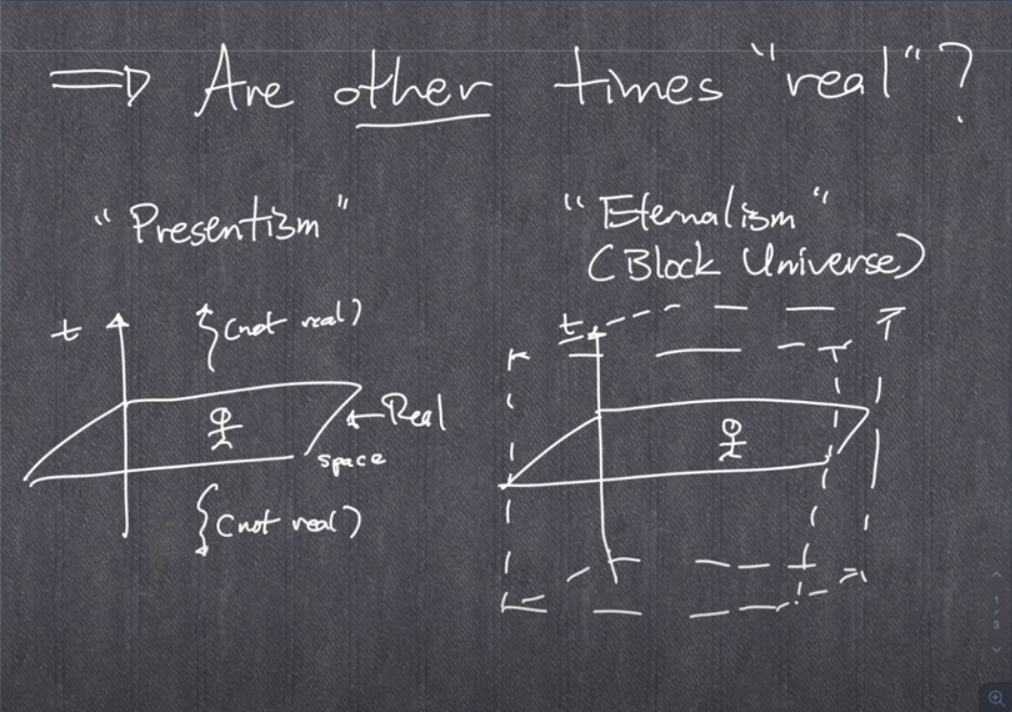

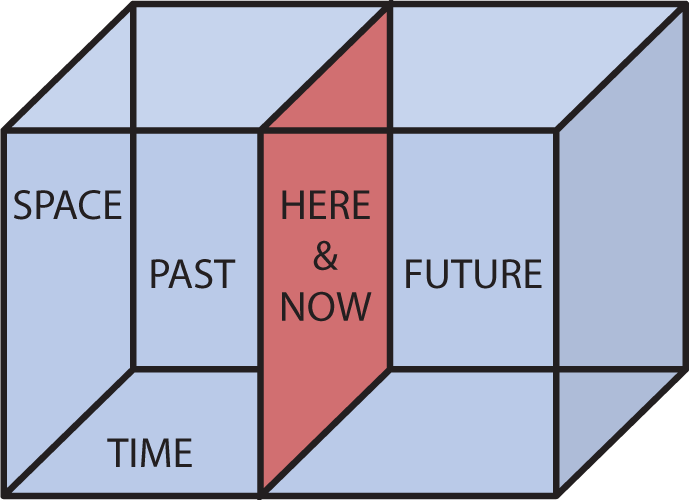

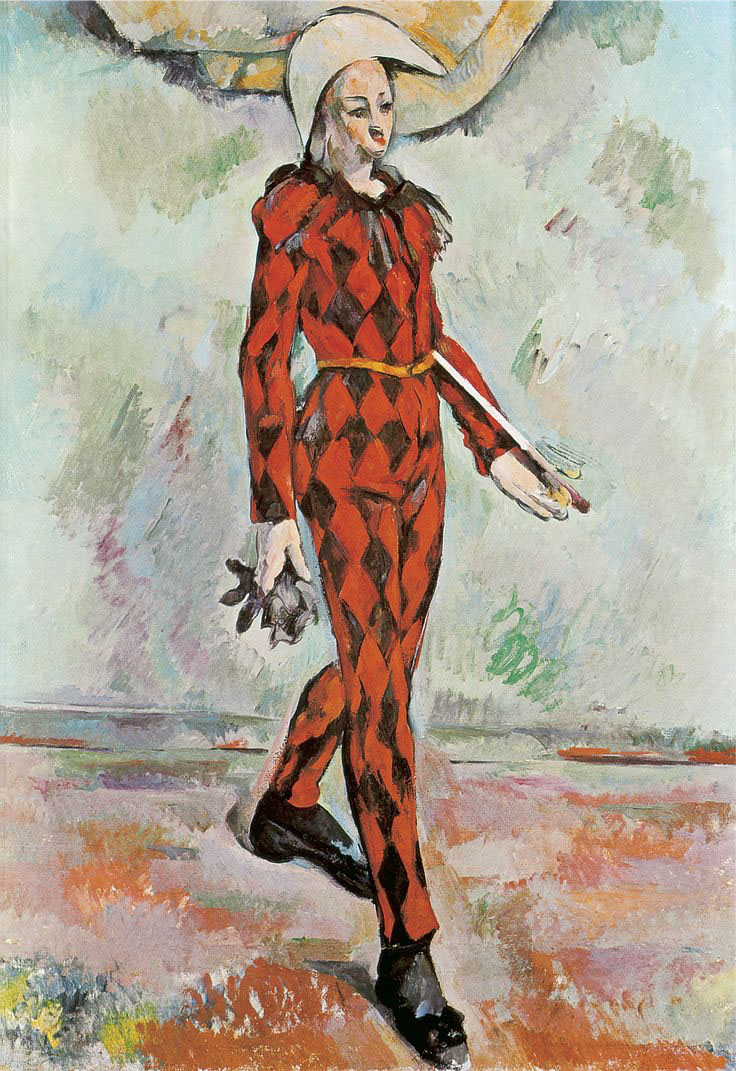

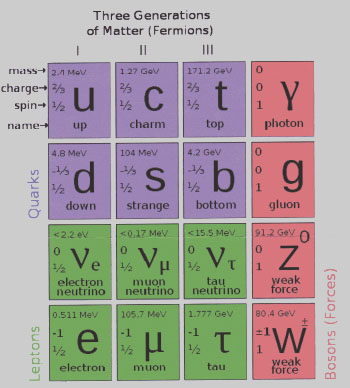

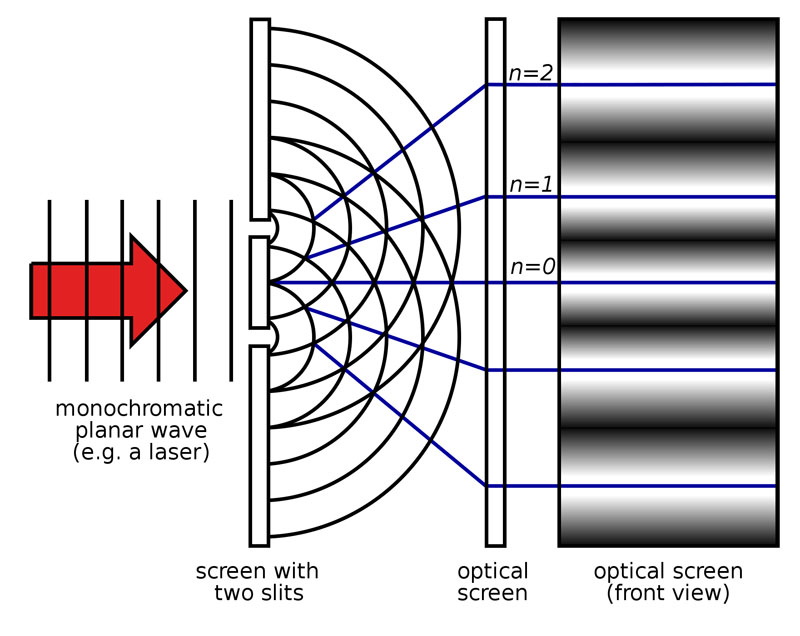

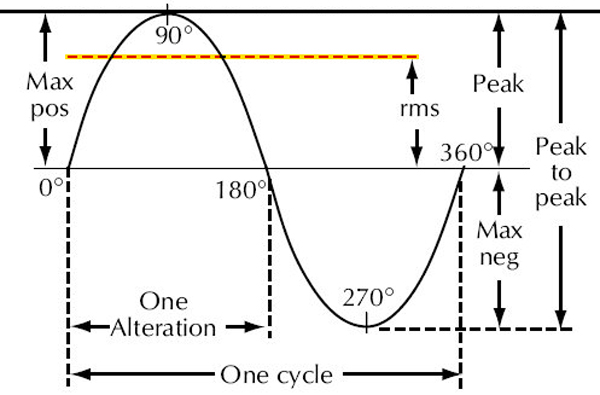

There are other views of how time might function explained by Mr Carroll but so complicated that all I can do is daydream them and should you wish to grasp the Block universe, (diagrams above from Mr Carroll) where the future is as real as the past v only the past is real, you'll have to listen to his explanations rather than a list of my responses which I'll spare you. That said I might well be unscientific because of my personal preference for truths that we sometimes see in art.

Linking space-time, block universes, many worlds, et al with The Golden Bowl, Lessness and my response to Bellini's Doge of Venice is my attempt to inject thinking into the art I try to make. Uncertain if I have failed so far hangs around in my thoughts and time's nearly up. [ho ho] Not giving up on the pursuit of grasping what understanding is, remains and is an enjoyable battle.

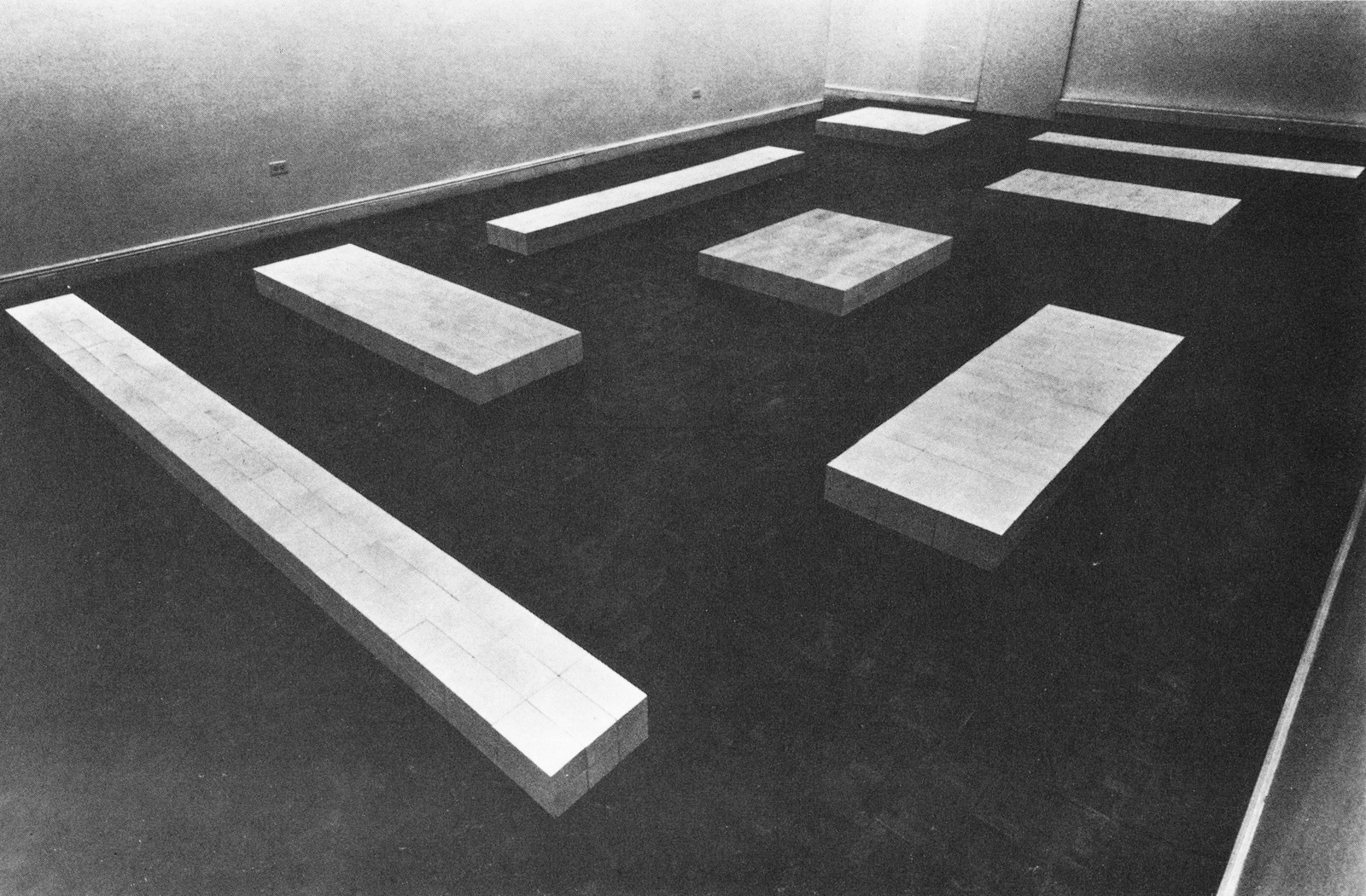

This box diagram seems a poor image with which to conjure my time spent looking …

… though it's interesting if one extends it to the array of boxes in Donald Judd's installation at Marfa in Texas. I cannot remember exactly the 'now' planes that exist inside Mr Judd's boxes but still recall the immense feeling the installation conjured making me dream of being both inside and outside of time and space.

Trying to follow Mr Carroll, I'm listening to his lectures again this time along side James Joyce's 'Ulysses' which is giving me fresh thought about how far our lives are away from what makes them possible. It's a shame that religions hang on to old texts as clearly a deity, if there is one, must have known at the time of creation that our biology would really struggle with a leap from classical to quantum. It might seem strange in the block universe to believe backwards … that thought would leave as well as arrive. Placing religious thinking alongside, inside even, the swop from classic to quantum requires new texts alongside as well as inside time. Finding out that we weren't at the centre of things was a shock, that the universe is unthinkably sized, that we are so minute, that classical thinking is in the past … well nearly … umm … makes one think a deity may well have other things on its mind besides us. A deity who knew everything about not just us but everything would have no curiosity and so perhaps could not make art.

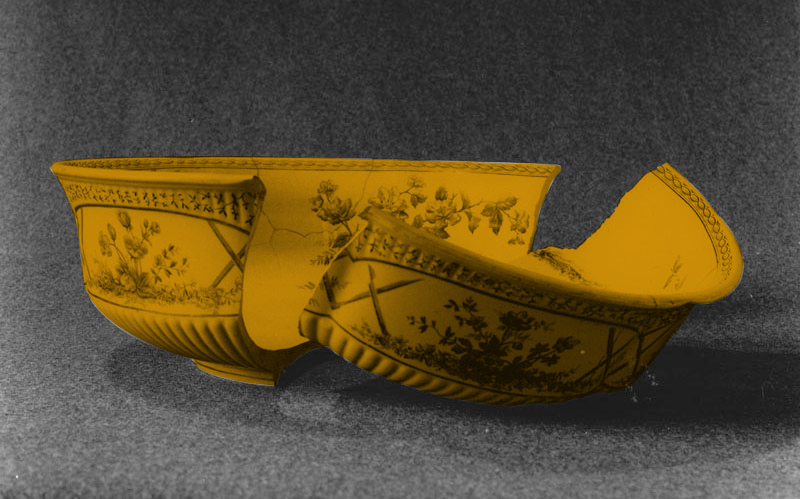

Soon after Fanny Assingham breaks the Golden bowl Adam and Charlotte Verver leave for America, the broken parts are left behind …

This is my very own broken bowl. It fell apart in 1976 when time altered as my belief in friendship needed rethinking. When Maggie knew that lies of omission might break her father's heart, as they might well have already broken hers, she waited in time. Henry James embedded Maggie's lines in Art rather than therapeutic treaties because Art, like prayer, is an act of love rather than petition.

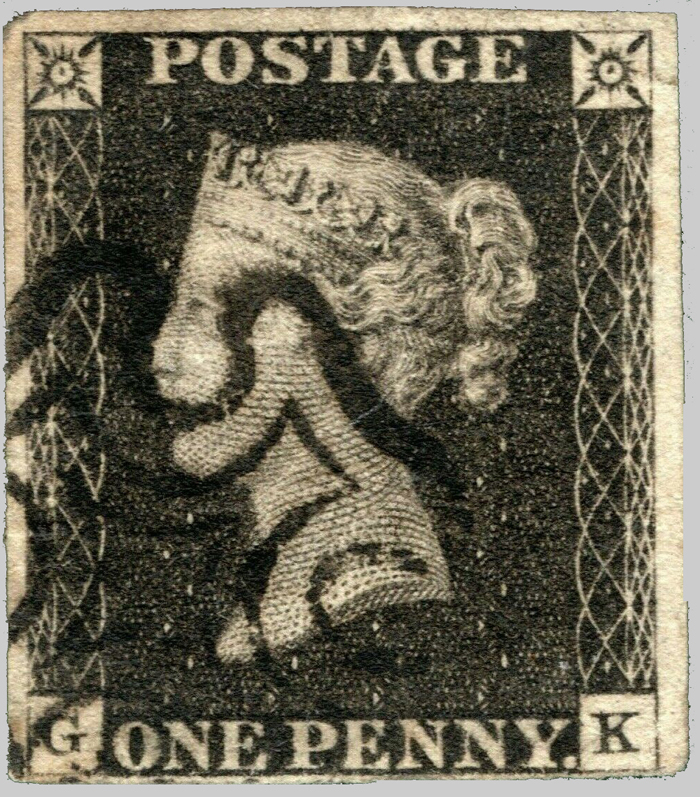

Stamps.

As a child 'The Three Musketeers' Stamp Club' was pencilled onto a wall where I met with fellow collectors; we wanted, no dreamed of a desire, at the very least, to see a Penny Black. These days I can see an image of a penny black with a few flicks of the keys, even read of another Wallace who pioneered our postal system. When I wrote 'Six Letters' (elsewhere on this website), HV3, as I called him, sent letters to his six wives and used stamps until he got to his last wife Katherine Parr and there were no stamps left, instead she had to 'Burn the Rose'. The other thirty letters in that work are, in a way, also fake because I never sent them, they too 'Burn the Rose'.

What I wonder connects being a child and wanting to see a Penny Black with my memory of being a child and wanting to see a Penny Black? What connects a rose with a burning? Perhaps artists make works without knowing why and does that mean they are obscure, difficult and sometimes unfinished because one kind of thinking sits badly with another. A visual artist may embark on a work wordlessly; when asked "What's…?" the visual thought is passed to words and may cause a snap.

I had a snap when post art school I thought to enter the 'Art World' but like skimming Earth's atmosphere attempting entry I was left high and dry. Still in pursuit of art the feeling I get when/if I manage to step inside a work remains to this day, I am content. It no longer matters that I never struck gold, if that's how it feels for those who have. What I have is the opportunity each day as I work to think about my past. 'The Three Musketeers Stamp Club' was little to do with posting letters but more the cultures of collecting; my painted past may have little to do with success in a gallery but more to do with my private life. Many painters hope their works will be paid for as well as collected, we all need to make ends meet.

During the repetitive parts of my work I listen to talking books and so heard of Charlotte Stant in Henry James' Golden Bowl; it was a moment of externalising, seeing myself perhaps as others had. A ghost of myself was being handed to me by the great writer as he presented perhaps a way of thinking about how we can attempt to live well. As a child Adam Verver, Charlotte's husband, may have begun his collections with stamps and I wondered if he had owned a penny black because he could; if he had married Charlotte because he could or perhaps for the Prince; if he had loved his daughter because, unlike his wife, she loved him. We attempt to understand our relationships but like time they/it passes without us knowing its speed or direction … that our feelings vanish when we die. Well aware of the cracks like those of the Golden Bowl I try to see; seeing is my pleasure.

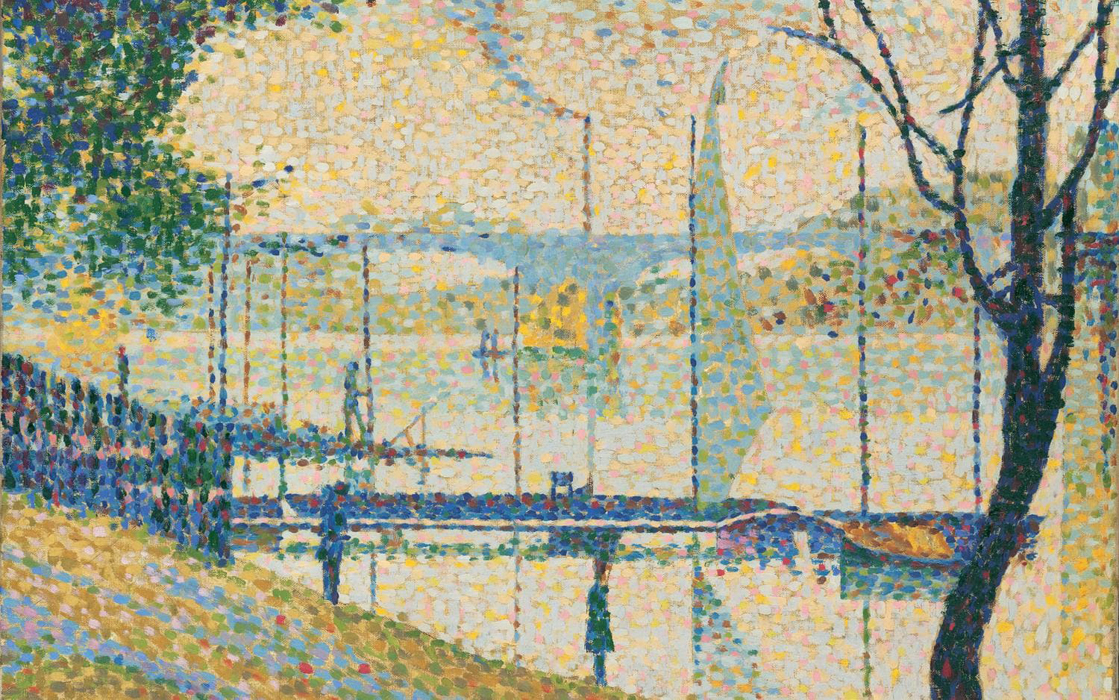

This Charlotte moment shares the coloured dots I am applying as I continue my way through the 'Bowl' hoping to come to terms with failures from my past…

"Well now I must tell you, for I want to be absolutely honest… I don't want to pretend and I can't pretend a moment longer. You may think of me what you will but I don't care … I came back for this and not really anything else. For this … to have one hour alone with you"

Soave sia il vento

(Gentle be the wind)

In 'À la Recherche du Temps Perdu' Swann floats from one group to another with gentle ease until he falls in love with Odette, Madame Verdurin exhibits the cruelty she perhaps does not know she has. It's easy to dislike the shallow Madam V. to sympathise with Swann as he changes floating to anxious steps. For me the saddest thing is that he cannot manage grief alone but needs the help of others.

Groups come and go with us all, we might be within The Three Musketeers Stamp Club as children or even play Prisoners Base to capture one another until the tall man in the top hat, Swann, arrives to free his daughter and return her safely home. Proust's work wove itself into my life over a number of years and I remember when Albertine first died I stopped work and paced the room stunned that she was no more. Listening more than once, she has died many times and for others too but my first time was a heart beating fast moment until a notion struck me. I walked to my player removed the disc and replaced it with an earlier one … Albertine lived and led me to the book I made … 'Albertine's Truth'. I also painted 'Albertine's Truth' but no longer hold the memory of its orange colour until I travel to London where it hangs behind a sofa.

It seems to me that Swann appears in Proust's work as the ghost of the narrator. I love the presence he brings, first when he enters through a garden gate to the sound of a bell and into a small family group. Then later in appearances with 'The Little Group' of that self-seeking Madam Verdurin where he faces the issue of 'where do I belong' v 'who do I truly love'.

He, Swann, may have been depicted in a work by Renoir binding in another way our fiction with reality, at the back of course with his top hat and his sorrow. That sorrow touched me deeply; I imagine him paused, frozen in time with the forgotten Bergson but I thank him beyond measure for this: -

"To think that I wasted years of my life, that I wanted to die, that I felt my deepest love, for a woman who did not appeal to me, who wasn't even my type!"

"Rudy beag bocht

(poor little Rudy)

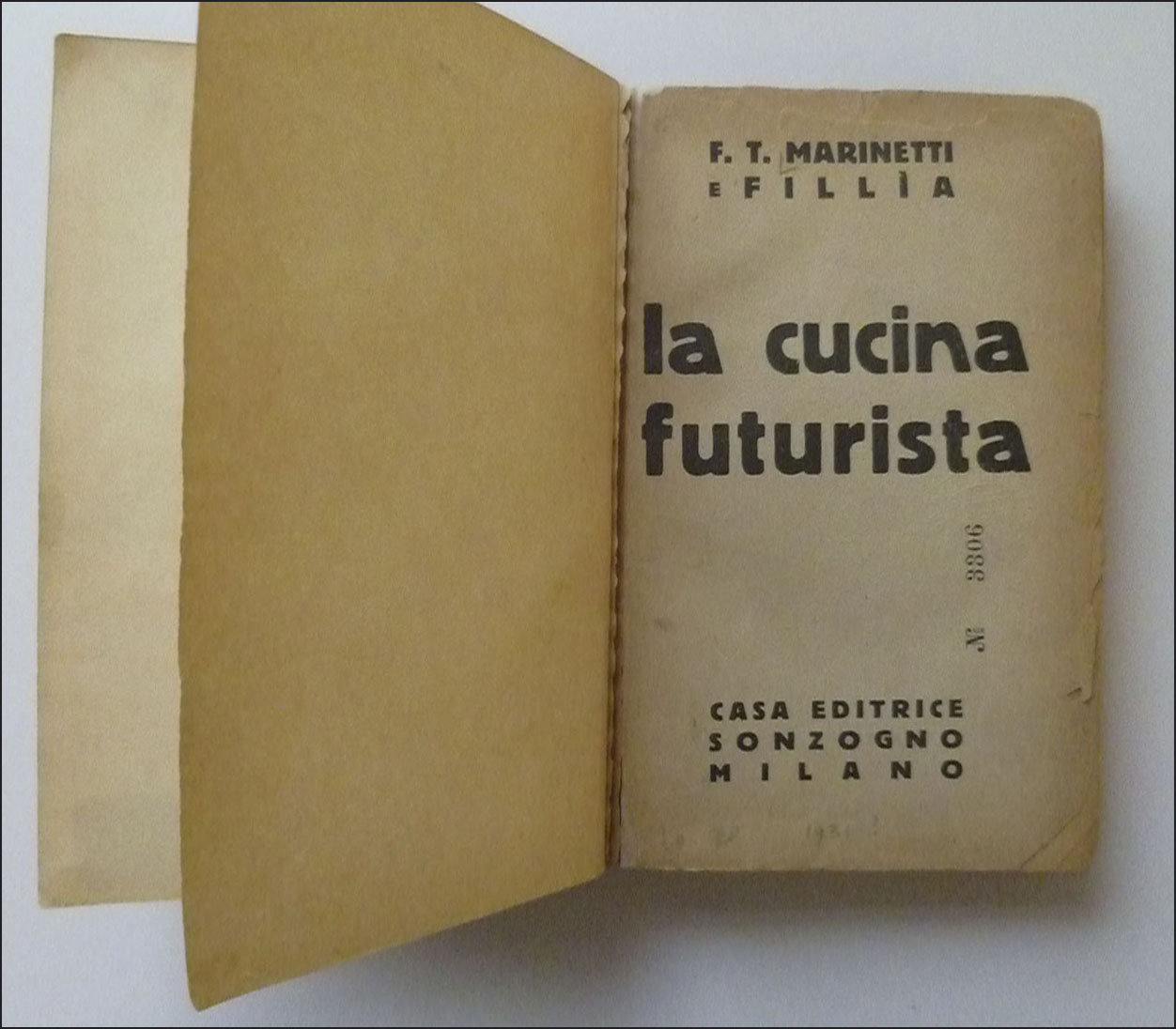

Like the forgotten Henri Bergson I feel differences in time rather than a variation in its speed. So listening to a reading of James Joyce's Ulysses as I tinkered with my task I felt a little odd, was I still fifteen and making decorative objects for presents. My left overs would certainly be similar to many others we sweep up; I wonder about our left over fragments, even go as far as to imagine a row of boxes filled with their differences … say the bits chipped off the Apollo Belvedere, bronze fillings from a Henry Moore even the crumbs from a gorgonzola sandwich with a trace of mustard left by Leopold Bloom.

"But you know I'm so glad to be on my own" is a line from a song; it continues "Still somehow the slightest touch of a stranger can set up trembling in my bones". As Bloom wanders the Dublin streets he might dwell upon these sentiments; has he, like Joni Michel who sings the song, made an exodus from his loved one or has the loved one evaporated? Bloom is left with a ghost of himself he cannot bear to see; that ghost, Blazes Boylan, folds the voluptuous Molly into a gin and splash that he offers to the side-lined husband. Bloom fears the intimacy he had shared with Molly for though still in love with her he's constantly forced to be on the fringes of her thoughts. In their bedroom, always knowing that one of them is upside down, Bloom sleeps as Molly dreams or is that the other way round. In that other Ulysses book, perhaps Bloom would be the one who unpicks the past days work.

Were I to submit my fragments for others to see, 'Post Modern' as it were, I would be refused an entrance and so, like Daedalus, gradually become aware of my own stamp … Penny Black- Broken Crack - Wrong Track -Thinking Slack -Tic Tac - Nick Nack - Ack Ack.

"I fear those big words that make us so unhappy"

"Ineluctable modality of the visible; at least that if not more, thought through my eyes"

Scrolls.

Long ago in an episode of 'Hancock's 'alf hour' our protagonist reads a learned tome but soon, to audience mirth, ends up reading the dictionary. New words pop out from Will Self, well new to me at any rate; there are times when I think he has them all tucked away in a secret place where the rest of us can't quite see. More of a dyslectic listener than a reader I have heard more than read the wondrous Mr Self. Rather to my annoyance, like Hancock, I have to stop his flow and look up the parts of his vocabulary that will never belong to me.

A close call was 'xxxxx' … well codex actually and I apologise to Mr Self for not having it logged. I'd hate to be on the wrong side of his meaning of codex so, incorrectly I expect, wander off into a 'text before books' meaning. Codex before paper folded in 'octavos' … Look that up in your Longer Oxford Mr Self. The history of paper almost certainly begins in China with wasp observations and for me at least has an ending of some sort or another when we left the elephant world for something not quite A1?

Imperial - Half Imperial – Elephant – Double Elephant – Atlas – Antiquarian et al – versus - A0 A1 A2 A3 A4 A5 … HUH

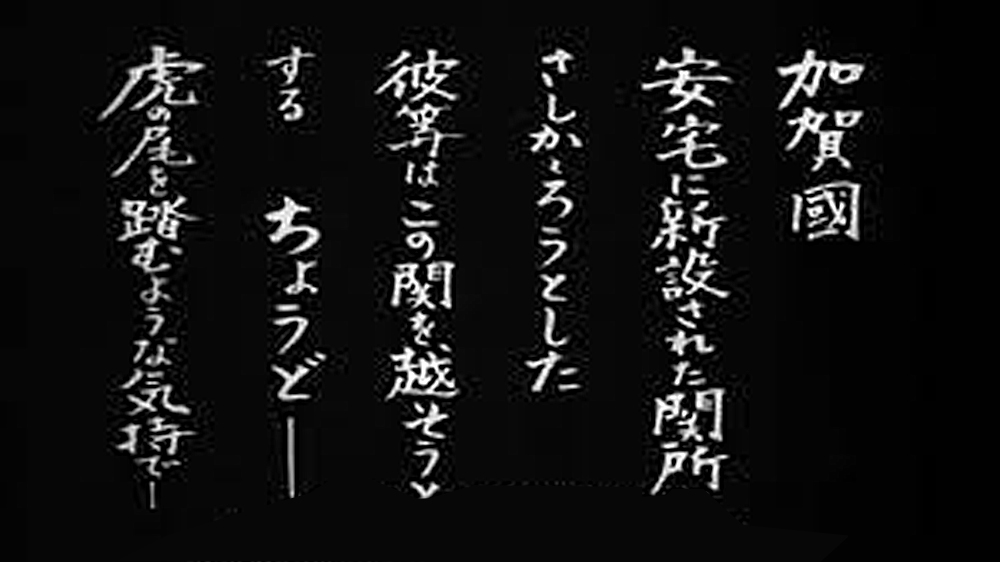

The paper I use rolls for my scrolls is Bockingford made in Somerset quite near the city of Wells. Sadly I have to have them cut on a mechanised saw that leaves me with imperfect edges unlike the preferred factory blade. I have been working on scrolls for a while now; there's something really appealing about the process. I, like many other artists, still use rectangles that make spaces for us to look through, into and at. I am probably working on my last few canvas rectangles as I have discovered time consuming scrolls. I think, if I finish any, they may be my best works. It's as if the late great Barnett Newman is looking down and whispering into my ear, "Looks like you finally found the route to your subject Andrew". There are always dangers with new ventures but to my mind it's essential to work at the edge … 'to walk on tiger tails'

With the unease of one about to tread on a tiger's tail.

I remember the 1952 Japanese film 'The men who tread on tiger's tails' where a scroll is read in dangerous circumstances in that there is nothing actually written and the reader is making up a text.

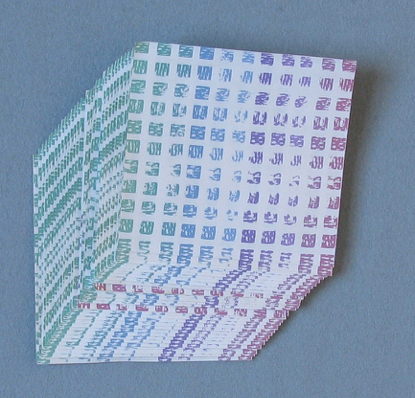

My early ventures into scrolls were tentative but my improvised actions led to this. What I didn't know was whether it was a complete format?

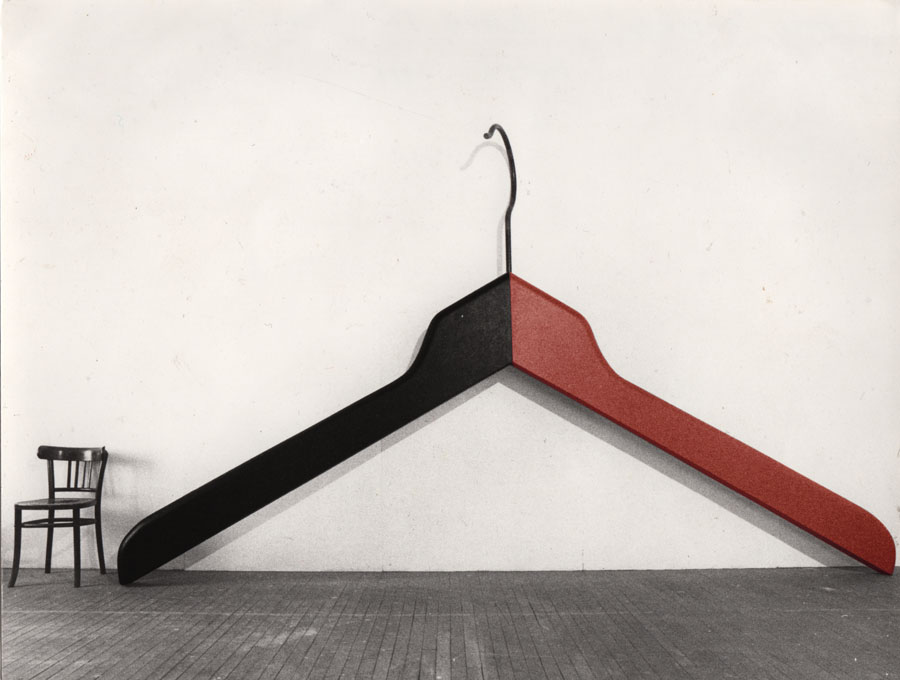

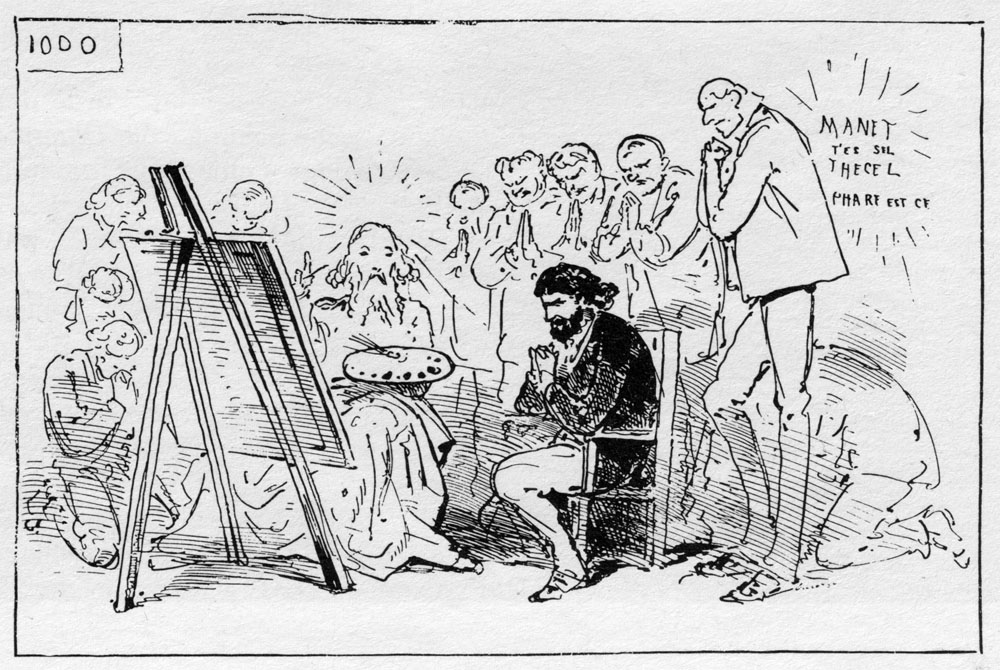

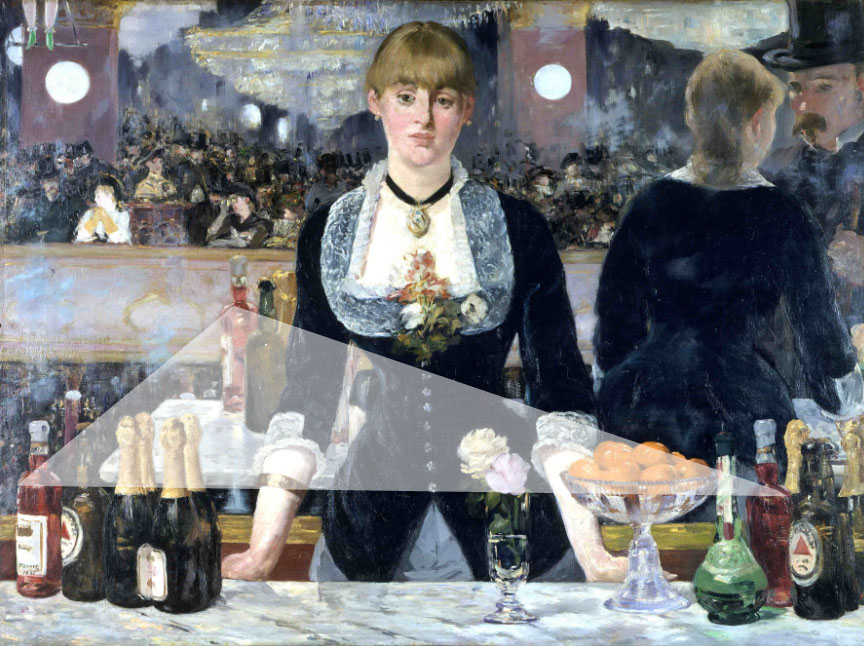

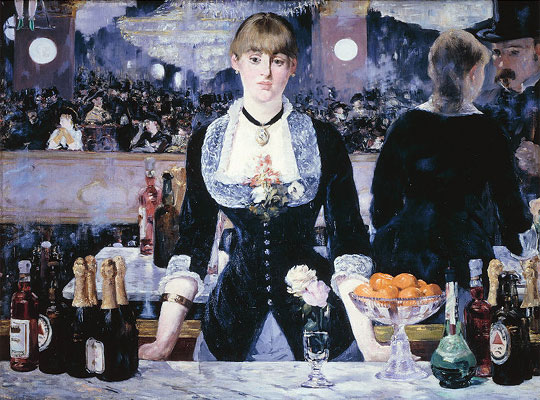

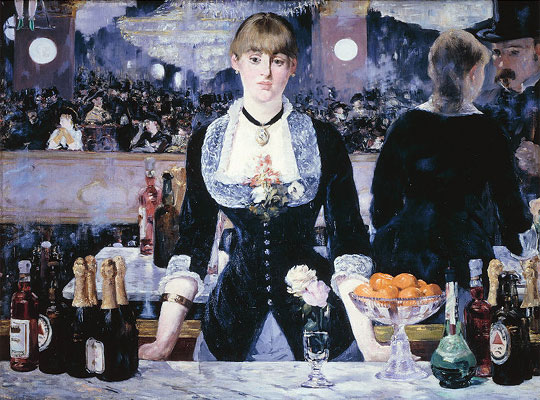

The rectangle problem is one described by Clement Greenberg in his 1948 essay 'The crisis of easel painting'. Manet is in there as he initiated a change than rocked the process of western art possibly leading to many artists leaving their rectangular tradition. What we have these days is the reproduction and edit difficulty brought to mind by Marcel Duchamp. Here's a later scroll example: -

and edit …

John Berger talks about the issue in his 1970s television series 'Ways of Seeing'. How easily edits work on camera but are differently available by eye when we are in front of the work itself; finding out how to look at a painting is difficult, we all need help. Television commentary is useful but tends to skip available differences focusing on the presenter's single view. To my mind unless we connect via looking when in front of the actual work the art remains as possibility, un-transferred as it were. With cultures embedded in rather than open to change it is easy for 'a looker' to seek contentment rather than participate in the effort that looking at current works demands.

But, and it's a big but, what we have to face is, do we need any longer to be with the actual work or see via the various ways we now have of reproduction? I have no answer and in a way, because it contradicts my belief in being with the work itself, am glad I don't have much time left to concern myself with such a huge issue.

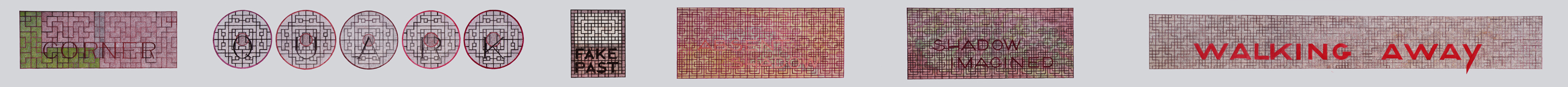

I can't quite grasp how or indeed whether I have happened upon this issue with my scroll works; perhaps that's why I think I have found something more pert than my canvas rectangles. Looking back at my first scroll venture it's easy to see a set of attempts to activate space/s, what I had to face up to was their separations … could they be cut up and placed side by side? What I love about my current thinking is that it hangs in the visual flank of thought unlike any other that has passed through me. I have stayed, perhaps for too long, in what I was taught many years ago, trapped between the culture and desire to be alike … to be with others.

In my scrolls I desire a continuous flow even though I am aware I am still using a rectangle albeit a long thin one. With this in mind I'm anxious to find a route that means the scroll is something other than a 'series of rectangles' separated but on the same sheet and into, at the very least, something that needs to have a 'walk on by' quality. This poor explanation only approaches the thought flank already mentioned.

Imagine scrolls arranged in a cylinder you have to duck to enter; I think that John Berger presented a work in this way and though it might work I try to dream up other ways to present. I'll keep edging my way hoping that when the tributaries end the river'll begin and I'll be sailing along it in an unknown direction.

Another way of getting my thinking mustered is via Amara, a girl of about twelve just after she arrived in London. She has her first ever day in an English school and is handed an exercise book … "Write your name on this Amara" - "aktub asmuk ealaa hadhih aleimarati" in Arabic … Amara wrote her name on the back or did she? The book as an object has two fronts; two backs one middle but my recent brush with Kierkegaard has given me another thought or two enlivened by the quote "Life can only be understood backwards; but must be lived forwards". I would like to make a scroll that could be opened from either end but sadly it cannot be done.

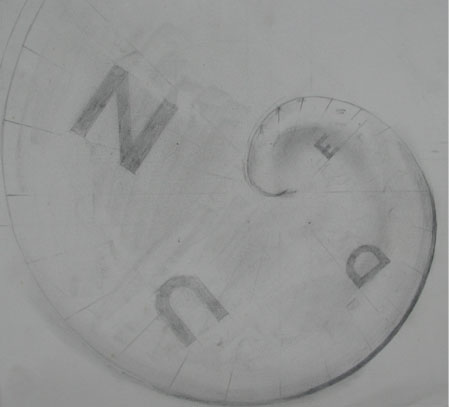

"Imagination dead imagine" this time a quote from Samuel Becket adds to my desire for circular thinking but I had a stroke of luck with a dyslectic error that led to an Homage to the great man. Here's how it happened …

I took this rather poor snap in my workroom and just in case you haven't noticed left out an I … AMBITON should of course be AMBITION. After the discovered error I pencilled 'Not I' … 'omage to Samuel Becket at the end and began the work again but this time added a different end and beginning.

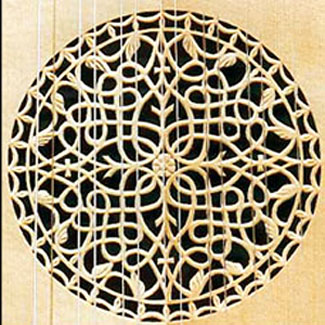

Though incomplete you can at least see the eye of Horus on the right and on the left the beginning of a Celtic Knot. My spelling mistake led me to an addition that took me a step closer to understanding what I was up to. This text is long enough for a single scroll so does not have the difficulty of separation as this one had done a few years ago.

As mentioned above this was an early attempt to link text that I had used in paintings and evoke connections because they are on the same sheet but I soon saw the problem that needs a better link than the paper they are painted on.

From above … and here's the detail problem again, images presented on screens versus 'being there': -

Should I use music 'dots' to help the flow from 'Inside the inside' and onto 'Hilbert's Hotel' I wonder? Well not so far as I have a slight fear of loosing the arrow before I have mastered how to draw the bow (Ref: - Zen and the Art of Archery).

I have found or rather am finding other linking thoughts and that is the wonder of old age. By now fairly certain that we are absurd and responsible for more than we admit I wander through the days longing to find out more … A worry though is that the Kierkegaard quote "Life can only be understood backwards…"

Do I need to understand before I proceed … umm … I think not or I would lose my tiger's tail.

Uncertain at St Dunstan's College.

During the non swinging years of the 60s I went to the Whitechapel Gallery; it was1961 and I'd read a newspaper article called 'Walls of Glass' about an art exhibition. Tweak this link and you'll see me as I looked back then at that exhibition, well it might be me, I'm uncertain. https://www.whitechapelgallery.org/exhibitions/rothko-in-britain/

It's hard to select a single trigger that got me away from one kind of life and into another but the gallery visit may have been one. In some ways half a dozen years of electrical apprenticeship were good for me but I was keen to find something different; we seldom truly commit to the things we are out of tune with. A mixture of chance and uncertainty got me into an art school; I was so naïve at that time I thought there was only one, such a lucky break then for a London Lad.

After the wonderful time spent in art school I needed a job and teaching offered part time employment that gave me days of the week to carry on with my own work. I spotted an advert in a newspaper for a part time craft teacher, after a couple of interviews I became a teacher in the junior department at St Dunstan's College. The vacancy included some art teaching though I preferred craft where children stand a better chance of learning to look, making objects rather than images. Making things that can be painted made more visual sense to me though I hope I got better at an introduction to drawing and painting for children. To begin with there was a speed issue; seven year olds can go through quite a stack of paper in forty minuets … umm … making a flat disk spin with interchangeable coloured tops takes more time but is it an art or a craft lesson. There were many issues to deal with and as I learned how to get children hooked I began to look forward to the time I spent with them as well as the days spent working on my own.

Over the years encounters with other teachers led me to thinking about the education system that crams our brains with a high percentage of things many will seldom use in what ever our world of work turns out to be. Talking about education was only interesting with a few teachers and we helped each other in many ways. Class management was seldom discussed, some 'strict' teachers frightened children and some children frightened teachers. I was never strict but did get better at class management, I'm still unsure quite how.

There were some great teachers and some who were dreadful, most of us jogged along as average and I suppose that's the same for more or less all aspects of human endeavour. One of the things I grew to dislike was prize day; terms like winners and losers, good-better-best et al un-eased me. I only once found a good solution to my discomfort when I gave my own prize of 'Concord memorabilia' to the child whose end of term marks meant being in the seldom-mentioned middle. This is not an easy issue, in later years the school came up with 'records of achievement' something for everyone but that seemed to me to be a crap idea too. I liked a notion I had back then which was complicated but boiled down to chance; my head of department thought it was hilarious.

Antony Seldon was deputy head for a while; during his stay the school became buzzy and we got an opportunity for a Lord Mayors Float through the city. I was asked to join the team and remember my list of suggestions at an early meeting, one of which was that we make a hot air balloon en route launched near the end of the route. "Totally Barking" came from Mr Seldon "That's why we want you in the team Andrew"; what I was really there for was to make the entry. The whole episode was a fascinating insight for me into the world of management.

It was easy to see that Mr Seldon was good at the system we had, as said he made the atmosphere buzzy but as we all do he had flaws … umm … I think in his mind academic achievement was the zenith. I wonder why the academic is used as the judgement for our intelligence when for many of us the time might be better spent finding out what you're good at rather than bad at.

Were education to be addressed to the many rather than the few there would be quite a number of changes to the curriculum. Here's a simple example with mathematics; there is a hidden change in maths somewhere among our years at school from calculation to maths itself … not entirely dissimilar to the change from colouring in to art. I witnessed a child made things with millimetre accuracy whose maths was described as poor. Of course we need to calculate but few of us encounter surds or calculus in our employments. Personally I loved geometry though algebra and trigonometry were and still remain an anathema of the time I'd rather have spent with Euclid.

All through the years I worked at St Dunstan's College I was 'light relief'; watching the way it worked was a revelation. As a minorities teacher all that really mattered was my relation to the children. I had no interest in it's being a career, as my brother once remarked, "in school there are HODs HOYs and HOBAs" … Heads of Department, Heads of Year and Heads of Bugger All. As previously stated there were, as in most of human activities, those who were good at it alongside those who were awful. What I learned through the years was quite remarkable; earwigging in the staff room was interesting but the children's revelations were quite, quite remarkable. Gradually I learned to see through and into the disguise of their language, what children reveal as they interact is often very different from what they say.

I try to remember the years of teaching children with warmth for all even though there were many whose grids were not aliened with mine. Each and every child will have a different truth from mine not only about each other but all of us who tried to nudge them towards an early response to how things operate.

As a schoolmaster I willingly learned to deal with uncertainty; watching children make things as a slow dawn. I was and still am uncertain about mistakes though at least I realize it's probably the same one over and over rather than the foolish pretence 'I won't make that one again'.

Children make fewer mistakes than those handed on by judgements from teachers and indeed many parents. This applies particularly to making things; 'which is the best?' alongside 'which is your favourite?' was a simple first step for me to deal with. Children find difficulty with these two 'Good – Better – Best and Good – Better – Favourite', as do some of us older responders. In art as well as craft this makes for real visual difficulties; sorting out what they are and how we educate remains unresolved. What exactly does "She/He's good at art' mean when there are no clear values/rules other than preference; it would seem that resorting to 'best depiction' remains even after a child has passed through the parental 'pin it on the fridge years'. The difficulties of looking, beauty, well made objects and art itself are not for children to unfathom though we might aim for a better set of responses for them to witness.

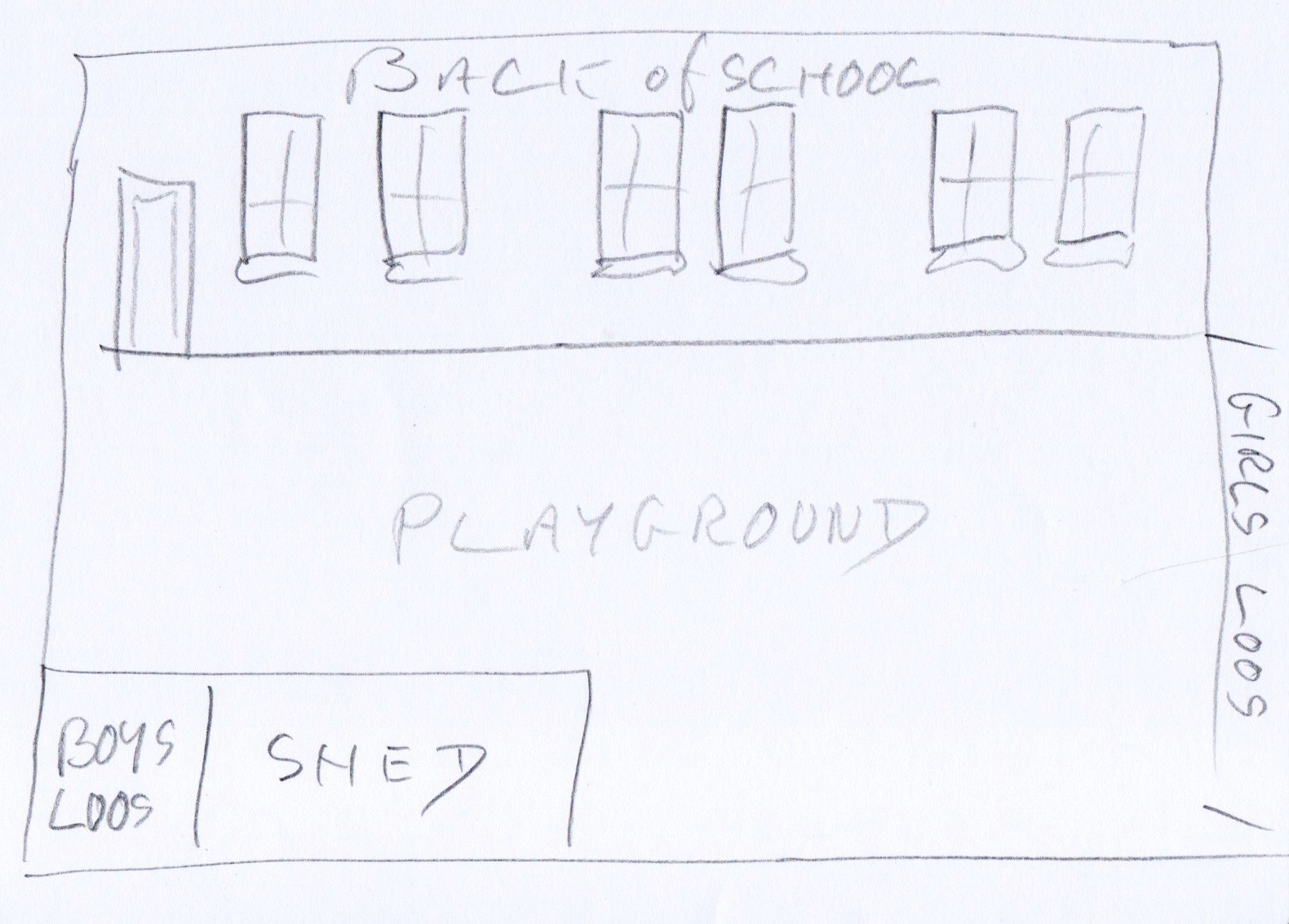

Hanging onto my uncertainty through the birth of our National Curriculum was tricky, the pretence that thinking is best when linear leads to despair for many children. Here's what my head teacher liked to see pinned up for 'Open Days': -

CLOCKS

1/ Idea sheets

(Draw as many ideas as you can think of for what you want your clock to look like)

2/ Two Favourites

(Study your first sheet and select your two favourites. Draw these two showing more details)

3/ Final Choice

(Make a detailed drawing of your favourite clock)

4/ Working clocks.

"That's lovely Andrew , parents'll love it" … of course I've left out many of the joys and sorrows that crop up when children made/make things. Clocks (in this case) where it's worth a mention of one girl's 'tear drop clock'; among the surround of muddled numbers she wrote and scribbled over "a time to cry"; her sheets of stages 1.2.3. were not inside her folder.

There's nothing wrong with stages '1.2.3.' thinking but it leaves many other pathways out. Unlike the scientist Hugh Everett, I do not begin to understand quantum thinking; even so I know that light takes all possible paths via a leaf on its route to photosynthesis and energy. Surely we need a rethink that includes rather than selects a single standard, if our leaders are of all one type it's because many 'average' children are neglected. In what became D.T. classes I used a few terms like these 'Oh no I've got to think', 'Make it work, make it look good' and 'Beware the delight of your first idea'; I hope these. Sometimes chanted or said with actions helped children thrill to the joy of making things though I lament my being less help with art in their early years.

As the years passed I gradually became a better teacher though I was never great as some I have seen in action, because I never fully committed; perhaps that's also why I'm the artist I am. Telling stories of teaching moments is almost certainly best left to writers like Gervase Phinn; he makes us smile, even laugh out loud.

So, my best efforts in the classroom were an introduction to making things, Craft rather than Art. A good start might be to change their titles though not like this … Craft became C.D.T. (craft design and technology) somewhere along the way the C was dropped along with finger dexterity and hands holding tools. D.T. design/technology, as it ended up, meant that most of the time a child spends is writing record sheets. There is nothing more likely to put many children off making things than record keeping. Records are wonderful as historic documents

but makers of objects leave objects for us to look at rather than read about. Of course records fascinate us when we happen upon them in museums or behind panelling but they defiantly put many children off the pleasure zones of construction.

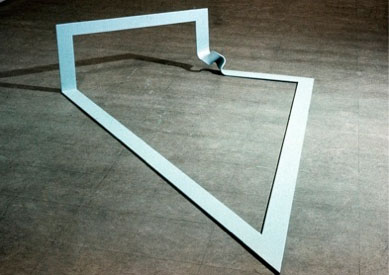

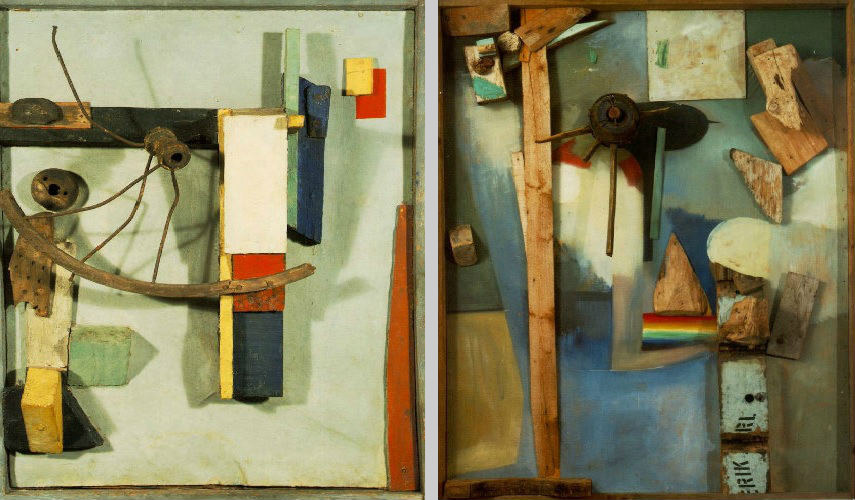

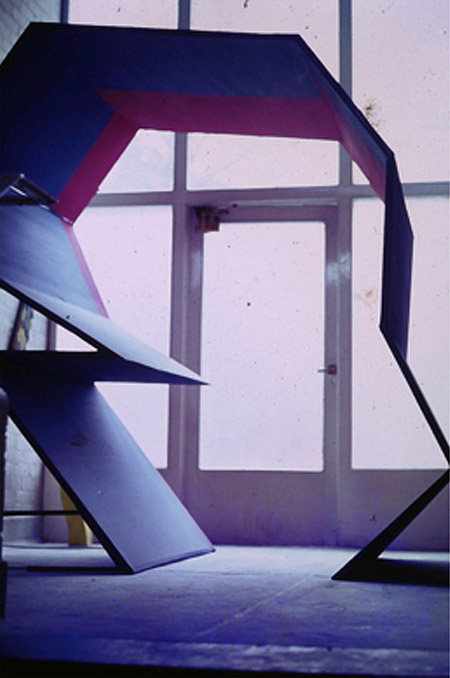

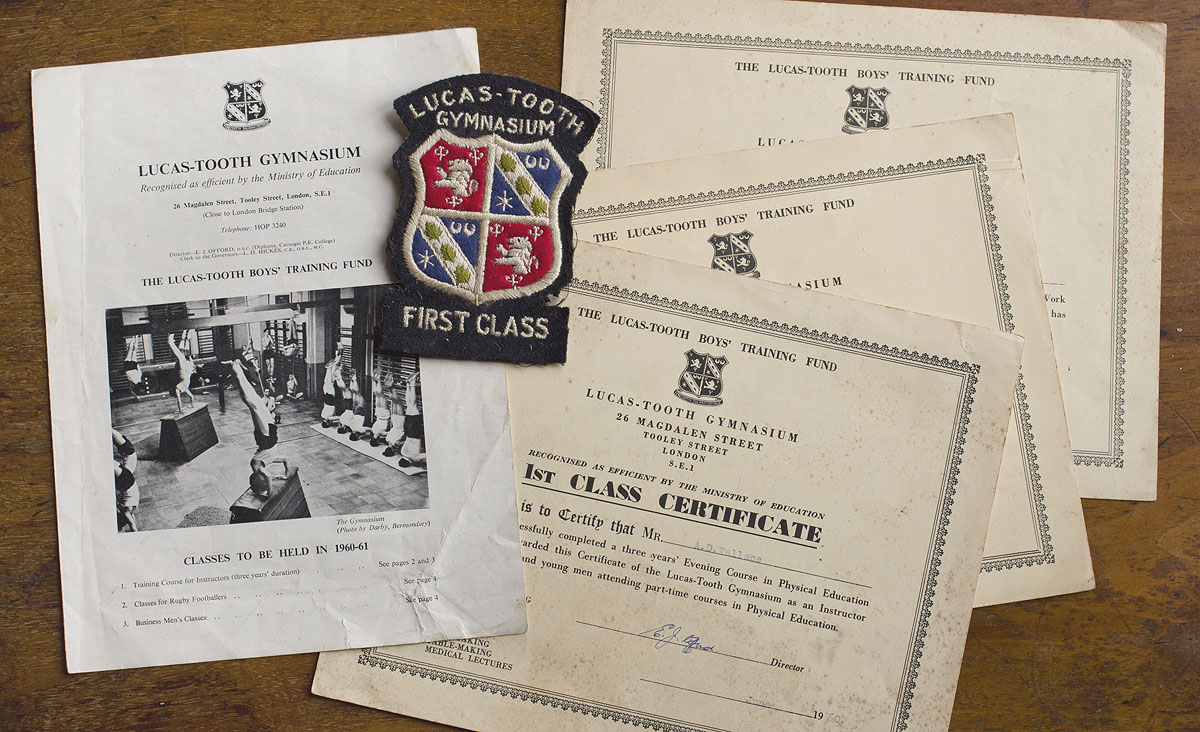

I seldom make plans for the things I make though there is nothing wrong with a route that does so (so none for the above, which I made in the early 1970s and still hold onto the buzz I got while making it). Isobel's 'teardrop' clock was beautiful even if there were no plans; the surprise for her was that I told her it was wonderful and that's because it was. Sadly I doubt many academic teachers would have rated it highly; there is great danger in the red pen, I became a truant because of its power over my emotions. One of my aims as a teacher was to have children in the room that didn't have the red pen sword of Damocles hanging above.

There are a few memory moments of my/the time I spent teaching, tucked away in the loft. One is the most wonderful set of records, even I can see they are great, made by an eight/nine year old; the sort of child loved by academics. These are superb sheets though I can't recall a single thing he made in three dimensions. My dozen or so 'Barry sheets' as I call them, if marked would be marred by red pen but still admired by the academic, recognition for Isobel's 'Tear Clock's beauty unnoticed.

I remain uncertain of a way ahead; certainty seems to me to be the road towards a dead end; looking at art can be hard work and distinguishing it from craft extremely muddled. Children may paint, draw and make things but to call their outcomes 'Art' plants misconceptions. My head teacher, bless him, would say pointing towards a wall space "can you put some Art there Andrew?" I dutifully pinned up things I knew he would like rather than the children's range of possibility.

I doubt there has ever been any 'Art' in a junior school no more than there has been great works of literature or breakthroughs in understanding string theory. What there was, was a range of possibility a chance; I once watched a girl construct a bridge, she was an intelligent maker; sadly after teacher and parent guidance she took to the well trodden path that neglects the full range of human response.

I loved watching children in my room of wonder, some were happy with 1.2.3. others with routes of their own while a few wandered around looking bewildered but possibly content with making nothing. I imagine in academic classrooms there were also children doing nothing though perhaps they spend time making headway with how to become invisible. Why do we only give gongs to 'top children' and later on to 'top people'; as the late great Richard Feynman points out "I've already had the prize".

I have to admit that I loved many of the children who spent time in 'my room'; I'm uncertain if they picked up a thing or two from me but I hope they remember vaguely. Things like, "An oasis in a sea of troubles" told to me on a train bound for Farnham School of Art by a lad I'd taught as a child, are rare but touching.

I thank both children and staff who worked with me at St Dunstan's College they were the years of …

"\Miracles and wonder" Paul.Simon.

PS

When I left my position was bombed and replaced by no one.

Good and Bad Government

I find it hard to picture Mr Rees-Mogg singing ‘See saw Marjory Daw’ to any of his six children but I can remember him laying back on the front bench of the Tory government seats. In Lorenzetti’s paintings of Good and Bad Government the depiction of Peace is also at rest though in this case not to show disdain.

Years ago we students were introduced to the Lorenzetti works during an art history lecture that prompted an interesting seminar with Nicky Gavron’ née Coates; interesting also because she left the art history department and took to politics becoming deputy Mayor for London. Like the rope that threads through the Lorenzetti allegory we leave trails that link our actions one with another.

The room where these works still ‘live’ is in Sienna, the Sala dei Novae (Council Room) of the Palazzo Pubblico (City Hall); it is said they were painted to remind ‘The Nine’ of their responsibilities. The Nine were elected magistrates who sat within the three murals depicting ‘The Allegory of Government’, ‘The Effects of Good Government’ and ‘The Effects of Bad Government’. The last being in a sorry state of repair, ironical because many of our world governments are presently in much the same state.

The majority of ‘public’ works from those times were concerned with religion so this one interests art historians because of its subject and commission. Imagine our own English Parliament commissioning art works to sit within. Rather than works like those of Lorenzetti I would suggest a swop to eight paintings by Ad Reinhardt.

Ad Reinhardt's have no illustrative qualities of the virtues, justice, wisdom et al in the same way as Lorenzetti presents them but they do contain visual messages. Writing an essay about these two artists is tricky; on screen one cannot get near the paint quality or be in the same space to let anything flow out from the work and into you.

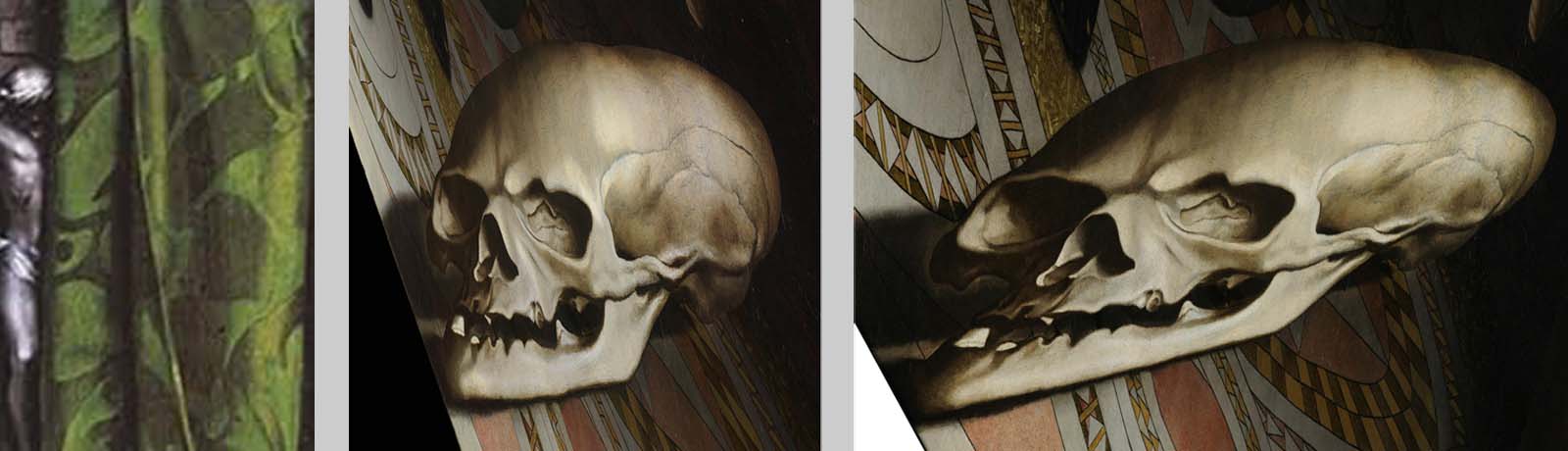

There was an enjoyable moment for me in a recent television programme when during an exchange between an art dealer and an art restorer the term "You've got a good eye" was used. The series of programmes follow the 'discovery' of a neglected work then through the highly skilled cleaning and restoration process to, hopefully, the restored status of a neglected work. Two easy aspects of 'A good eye' in this context may mean, firstly that the dealer has spotted a well-painted picture and secondly that the restorer has the skill to help us re-see its former glory. Matching pigments is always tricky but when a delicate work is being restored it's vital to be spot on; there are now machines that make possible, via spectroscopy, the analysis of original pigments used. Science plays a huge roll in the 'upkeep' of our treasures and certainly the great physicist Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman has lent a great deal to the analysis of used pigments; even so the touch of a skilled restorer with a 'good eye' is vital.

Lorenzetti was a thoughtful artist and when 'Bad Government' is restored the work will need a currently skilled 'painter' with a 'good eye'. The work, post restoration, will remain a Lorenzetti however and not have the name of the restorer added even though she/he might get a mention.

When the current government in Downing Street spent a large sum of money on a 'Briefing' room they might, but did not, have thought to add any form of allegory either new or restored that would remind them of 'The effects of good Government' or indeed 'The effects of bad Government'.

'See saw Marjory Daw' might seem a reasonable anthem for us to sing for our governments as they swing from right to left and back again …into and out of power. The desire to be fair for all our population seems remote from the current nine

Farnham school of Art

A large number of artist's web sites include the various places they taught; were I younger and not on the way out I may well do the same. Without any bullshit padding, the truth is I only really ever taught in two places and only well for parts of the times there anyway. Farnham School of art, now West Surrey College of Art, where I worked for close on twenty years was one of the two.

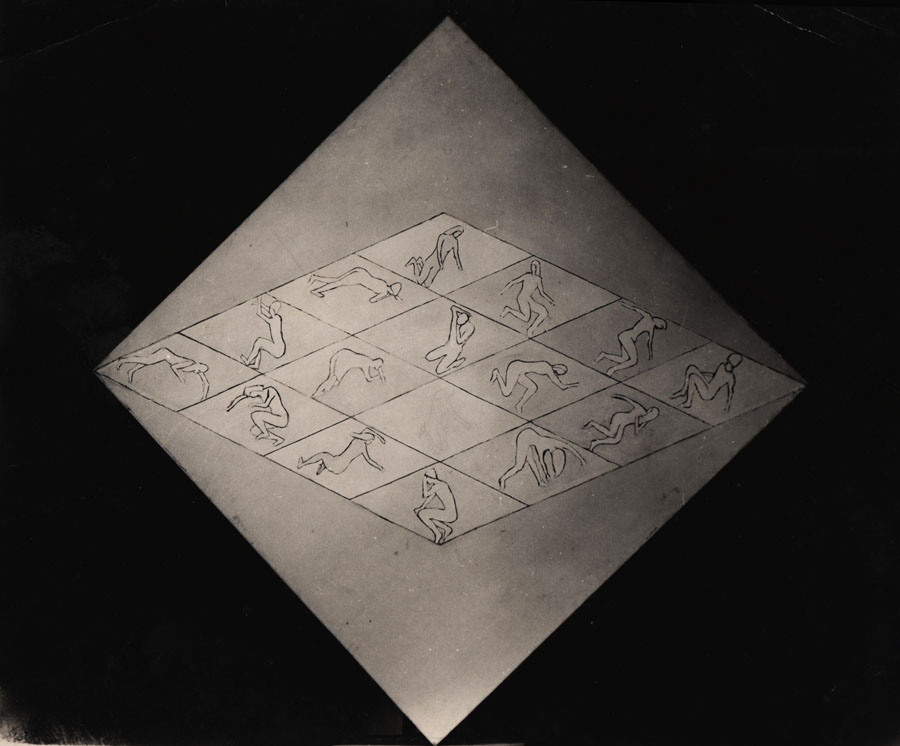

There were two main phases to the time I spent at Farnham; one was in the early years when I co taught, with Kay Fido, Performance Art as it was named back then. I have no idea if there are still classes in live performance art but there are plenty of videos being made. One of our early 1970s student performances, called 'Wall', has a 16MM film we made that I hope to locate and make available some day. The snap above was called 'Yellow Sock' and just goes to show how limited our means of recording was in those days, unless you had an interest in photography yourself and I admit to being hopeless with a camera.

Many students enjoyed the days we worked on this way of seeing the world and yet I was mostly nervous of pushing towards this particular edge of looking. Thinking back I think we ought perhaps to have made more tableaus; this form of art is not about the story telling and drama of theatre; Gilbert and George, two people one artist, made some performance works that reveal the difference between a visual based work and a word based one.

I know this is difficult because watching theatrical performance includes what it looks like but the essential elements are actors who speak. Performance art differs in that it is best at being still; were I to be working with students these days I would need to include a great deal of discussion on the nature of time. I believe that time is an essence of great works of art and students need to be introduced to its significance. I believe that this form of visual art began with Dada and continues to this day with artists like Marina Abramovic … well worth investigating.

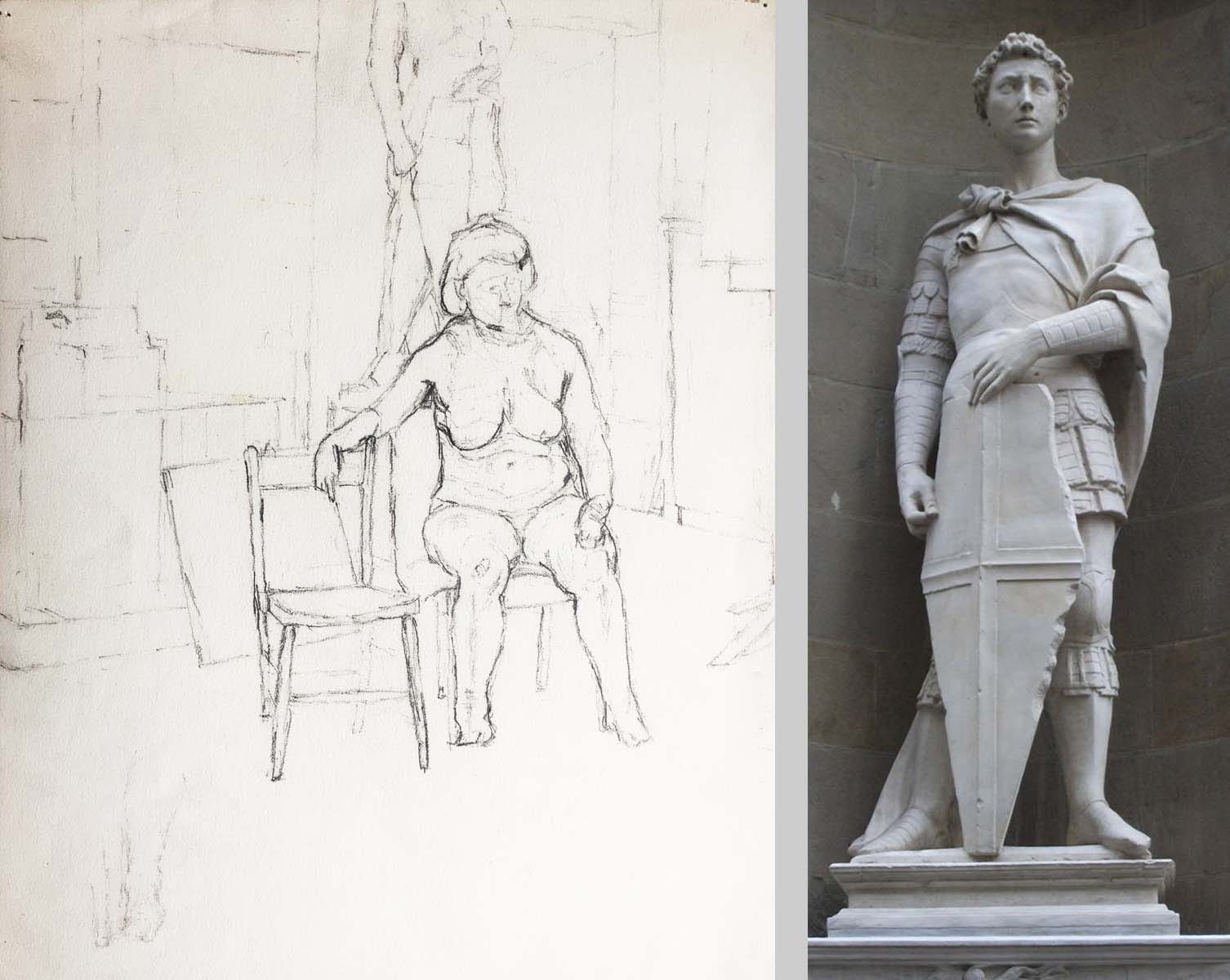

For a lot of the years at Farnham things in my personal life screwed up my desire to teach well. I just have to hope I was able to hold my distress at bay; having to focus on the well being of others certainly helped me. I am unsure how or why performance teaching came to an end but changes of department heads have their effects and it may have been one of these that lead to 'drawing day' being on a Thursday. I was lucky enough to have worked for quite a few years on that day, helping students to see differently as they learned to draw. To my mind there is no better way to make the necessary change from words to visual thinking than with pencils and paper.

Drawing in groups is different from doing so alone; the

atmosphere in a drawing class holds, I imagine, a special memory

for many people. There may well be other things we do together

that are moving, absorbing and fulfilling but to my mind finding

out how to look beats them all. We mostly see in order to

recognise objects; you can leave the room because you know what a

door looks like. Learning to see things as a whole, to become

aware of the space between them and the distance from where you

are, is made different when you learn to record what this means by

a description/depiction made with a pencil.

It is not unlike learning to read, swim or ride a bicycle in that

the moment you can do it is tricky to explain.

I may be wrong in my foot stamping that drawing is the best way to alter the way you see; art schools may now have other ways unknown to me where this change can be made but some how or other I doubt it. The important thing is to agree that seeing the world as objects is different from seeing it as 'space'. A problem with this is that drawing is a skill that needs practice but it also needs thinking and talent can be a danger, not always but sometimes. Being gifted makes it possible for steps to be left out "… he had the gift so it wasn't real art" says Molly Bloom in James Joyce's Ulysses. "Loosing the arrow before completing drawing the bow" from "Zen and the art of Archery" is another way of explaining that we need all the steps to get the final thing right.

We so admire skill that we may well stumble around trying to define exactly what it is. Belief that skill is art can well lead one up the wrong path. When teaching you have to keep trying to help students find their place, their process and not transfer your own way. I'm sure I failed many times but hope the ones who 'clicked' still enjoy seeing the world differently. This 'click' moment can vary considerably in the amount of time it takes but teacher and student have to commit for it to be possible. One thing I know for sure is once a student 'has clicked' with drawing, time alters. Perhaps because when you begin to see the world as space rather than as 'objects' you unfold for yourself something than cannot be said. I hope this doesn't sound to highfaluting but I believe those who believe that to be good at it is luck are just plain wrong; at the very least it's hard work and hard thinking.

"Then what is time?' If no one asks me I know what it is. If

I wish to explain to him who asks, I do not know".

Saint Augustine

"Then what is Art?' If no one asks me I know what it is. If I

wish to explain to those who ask, I do not know".

When art begins to flow from the work into your essence you have found a place to be still. It is the gift of very few to go on and make it flow for others.

I have no clear memory of conversations I had with students about these issues; most exchanges were concerned with the practice, how to hold the work open so you remain looking and not making a copy for example or how to alter things rather than erase them. Though I sometimes feel I'm getting close to deeper looking I'm sure many students went on to be far better artists than I have managed. Many, like myself, remain at pyramid levels below the pinnacle, loving the work but not quite good enough to make a step into the public domain. It's a difficult thing to think about showing your work and we can easily make mistakes.

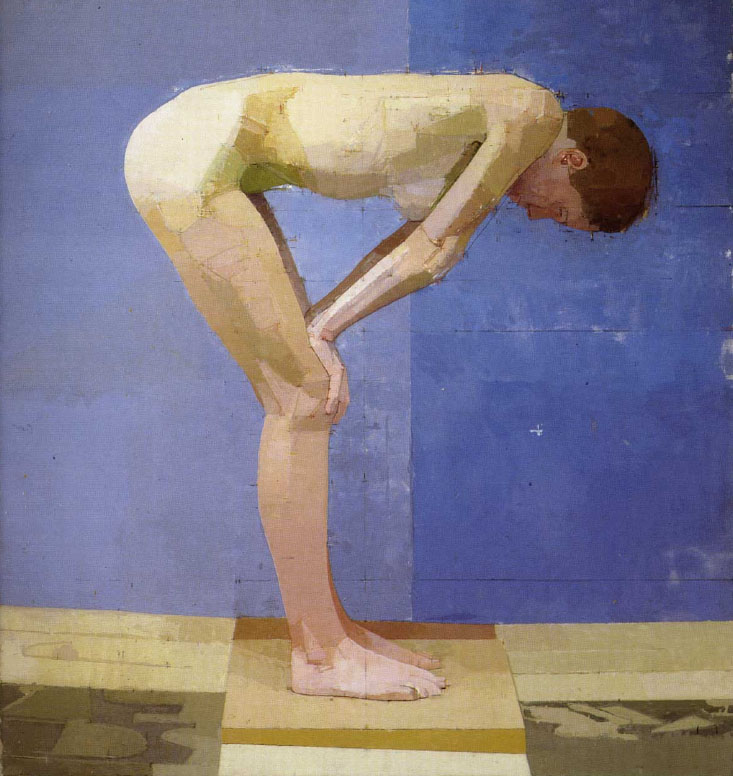

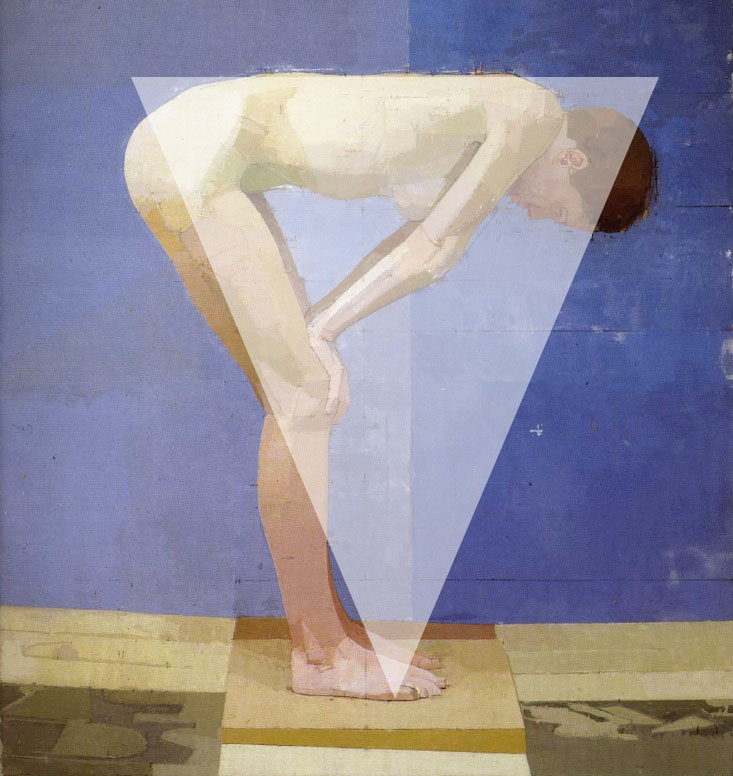

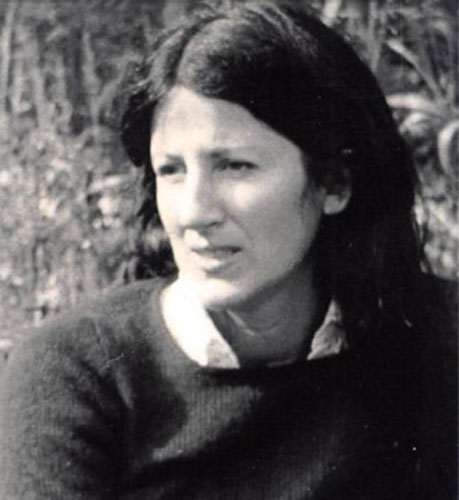

So many things are important when trying to put students into a place where they begin to see. One of the tricky ones I seem to remember is talking to a group and talking to individuals. Each student has to feel both special and a part of something else. I have three photographs of works by a young woman from my time at Farnham and hope she went on to enjoy a visual life; I found her fascinating because of her brilliance, her willingness to wait and her complete modesty.

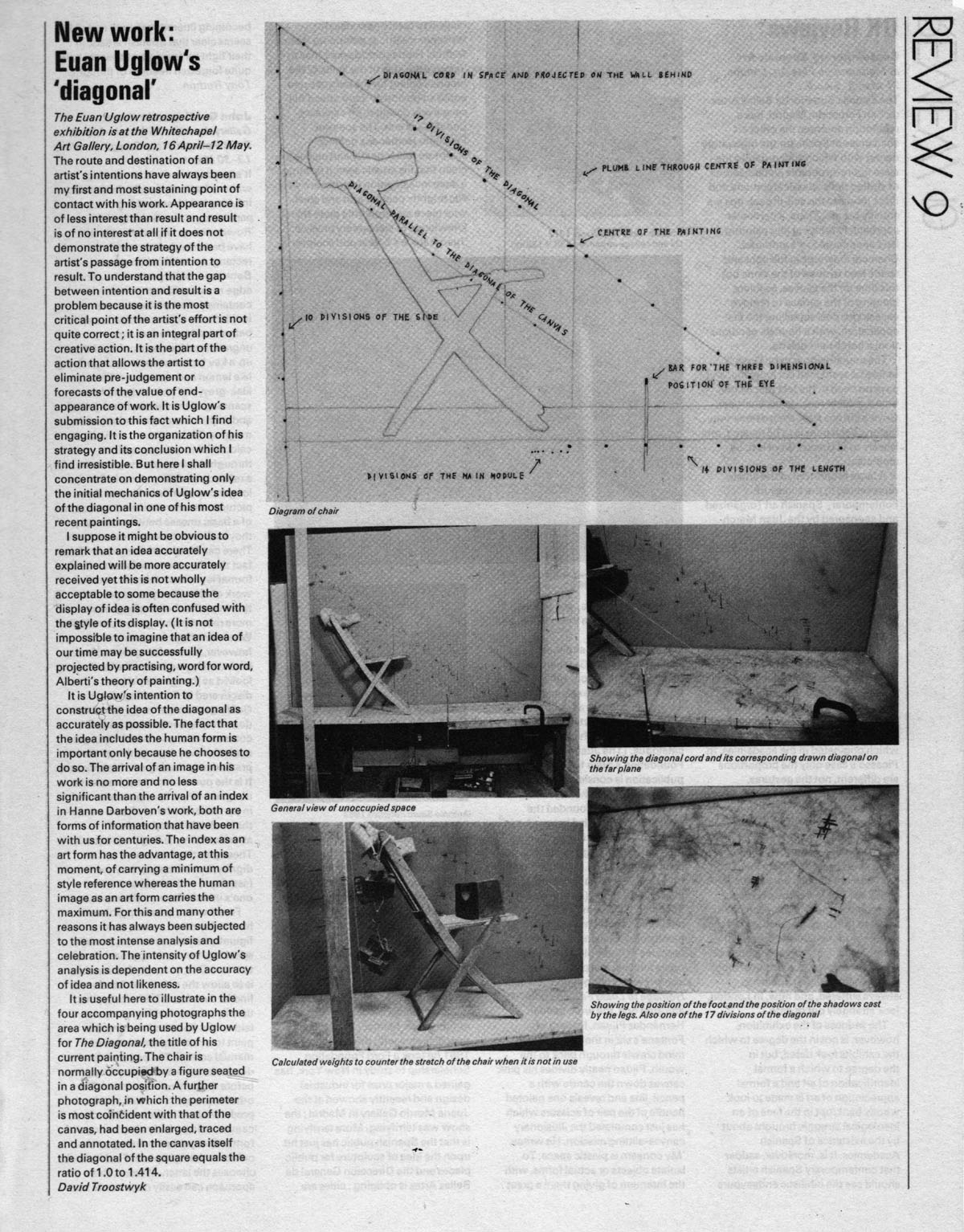

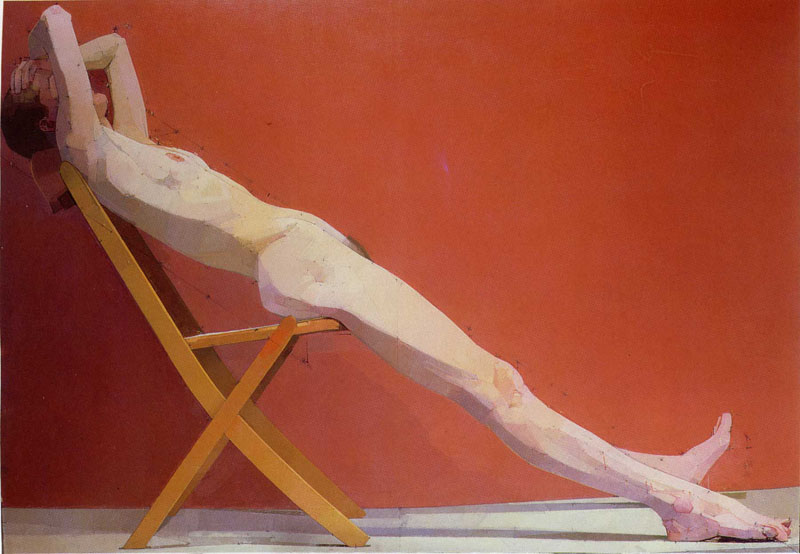

One of the things this woman quickly grasped was 'the rectangle' and its fundamental significance; one sees so many drawings that float in their rectangle. I remember Euan Uglow going on and on about this issue when I was a student and hope I managed to pass it down the line.

I tried not to repeat the subjects I set up from year to year though some blended into more than one theme. In the 'cubist year' I remember students being in a circle round a still life which I rotated a few degrees every twenty minutes or so until they had gone full circle. In the afternoon the subject remained still and the students moved from chair to chair round the subject. I wish I could see the results of this and hope I tried the same notion both early and late in the year's course. There are suddenly more and more memories popping back but it would be tedious to recall them all in this notation.

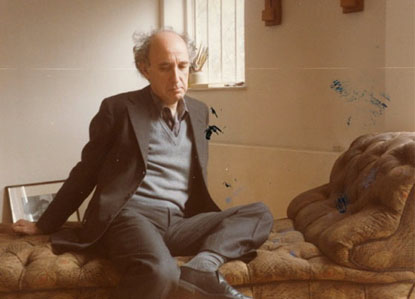

I was one of the mid eighties cut backs; I wasn't told, "You're no longer needed" but somehow or other I, along with others, knew it was over; it was almost certainly time for me to stop.

I loved the years I helped students with drawing though these days I wonder about the entropy in my classes … In thermodynamics you need a cold sink for things to function; in art you need a 'dump' even though there are elements you long to preserve. Keeping the fuel fresh is vital, so to my mind saying, 'It's new for them' ain't always good enough. It was just as well for me that I stopped teaching in art schools in the mid eighties; I was probably past my prime and needed to try something else.

Working Wall

This is a snap of a wall where I worked in the 1960/70s, a pretty grim snap I agree but it's one of very few I have. The thoughts it conjures are of me at another time when I was in another place. Since then trying to work out what art might be has been a fascination even if I can't fully explain what I've found out or for that matter very well delete.

I recently gave a talk to a small group of people in a science group I'd joined because I think that science gets as close to an understanding of 'where we are' as do the arts.

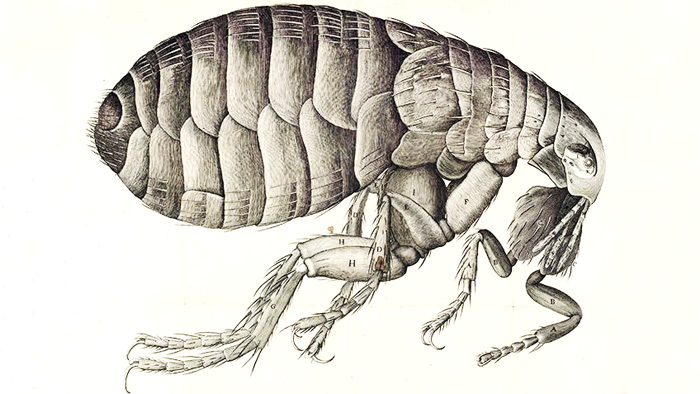

I kicked off with …

"At art school in the 1960s the nation was in the process of

swopping course titles and gongs and to my mind sadly, in art

schools anatomy was dropped from the curriculum. Anatomy is/was

an easy link between art and science … about seeing in order to

understand … we might refer to it as art illustrating rather

than art illustration but … "

Well something along those lines but the exciting part for me was linking, or trying to, Wolfgang's Pauli's exclusion principle with the kiss by Rodin and the decorative element in Gustav Klimt's painting of a kiss.

"Hold two strong magnets with like poles and try to push them together … now turn one round and recall a first kiss and the moment you both knew. Science and art are able to both repel and attract … unlike these magnets we are able to imagine and to actually feel a given strength…"

Slowly I began to lose my confidence picking up that this was not really going down that well. A zoetrope I'd made to show rotatory and linear forces was entertaining rather than engaging; umm I thought separation as well as fusion is a strong human quality. Stumbling on I got to the end …

"Years ago there was a public debate between Albert Einstein and Henri Bergson about the nature of time … science may be seen to speculate while in many ways the arts reflect so perhaps we could, with fusion, crack, the way time works..."

but it was a failure.

What do those old drawings and maquettes on 'my wall' have to do

with any of this? Well most of us are unsuccessful, after all

hardly anyone sees what we do. It used to bother me like mad that

no gallery owners floated through the window to my work rooms

declaring their joy. As a friend put it long ago, "Andrew, you're

a closet artist" and so I have always remained. The many artists

whose work is rarely seen may well be content as I am to get their

buzz from the work itself rather than the rounds of applause sort

by the pushy.

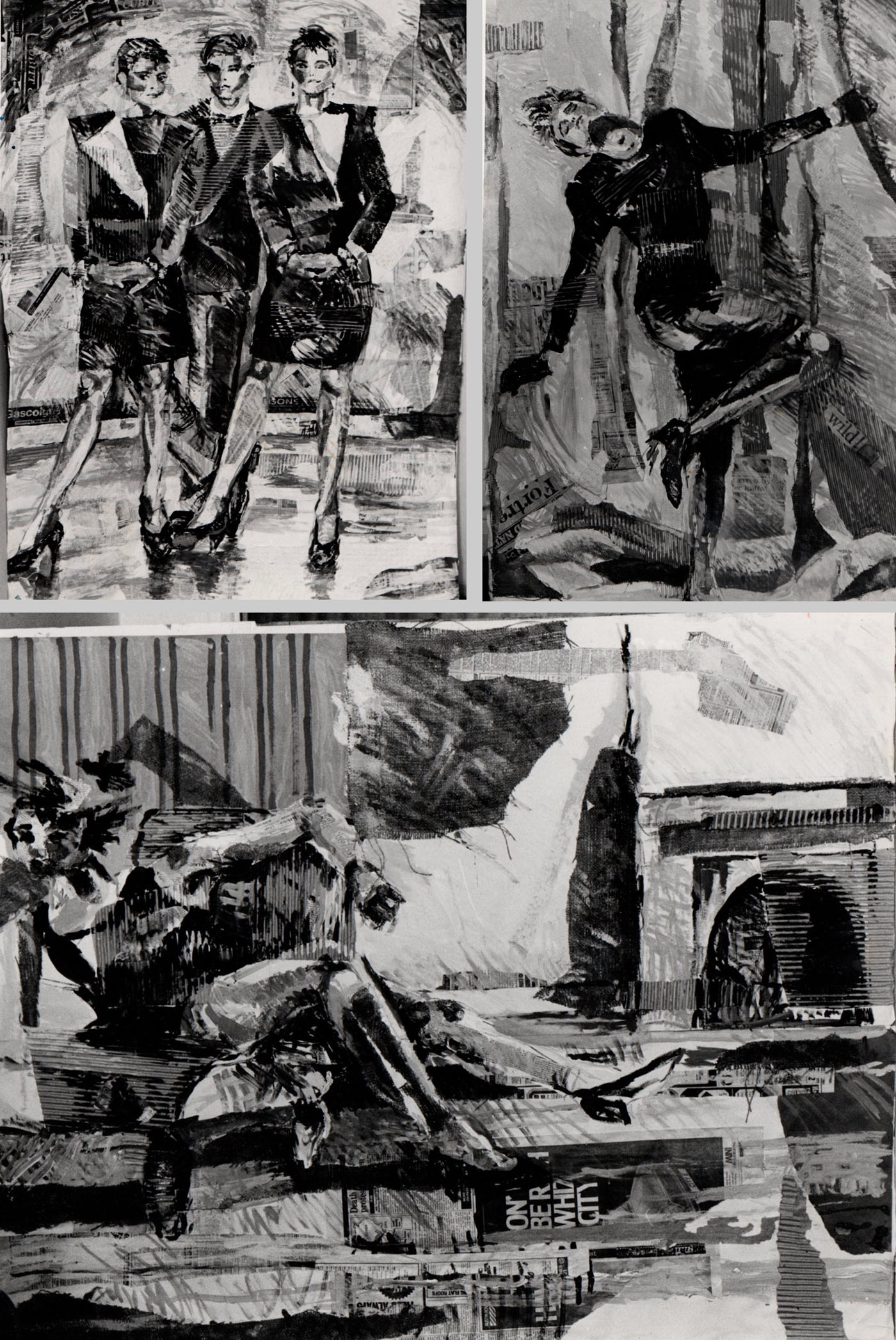

On one occasion when I worked at Farnham School of Art I asked the

students to read newspapers for ten minutes or so before a life

drawing class, they had to work out why I had requested them to do

this.

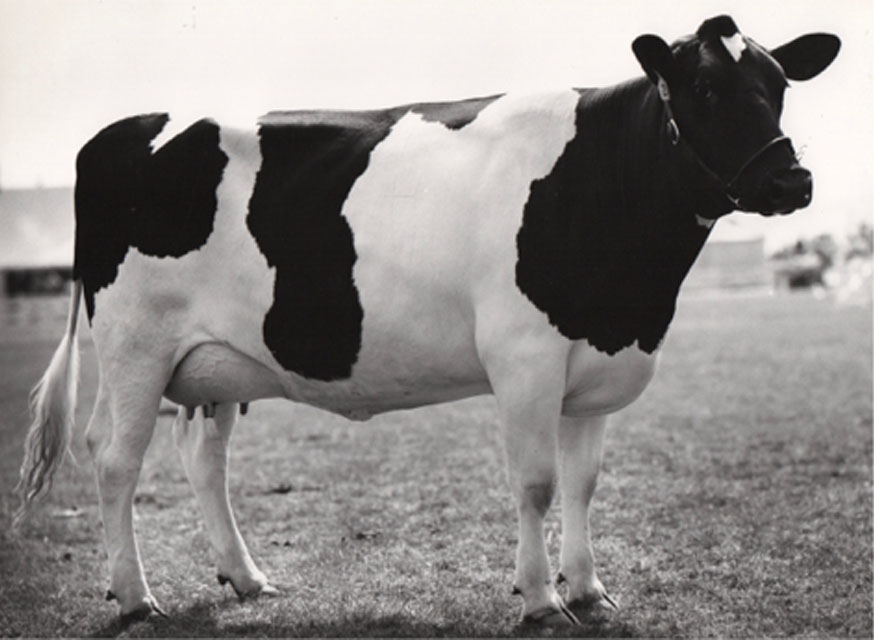

In our seesaw political systems where a nasty aspect of humanity

frequently dwells, most leaders are truly ghastly and yet they are

in continuance even on the increase. Magnanimous leaders are few

and far between leading to the fate of most people to be among a

few friends and acquaintances rather than happy within the

collective. I dislike capitalism and the conservative model of how

we should live and though held on high, the mantra, 'Democracy

Works' is a sacred cow failing to unite us.

Many of our leaders come from a tightly banded group of families

and schools who lie about their connection with the many. The Eton

school motto 'Floreat Etona' ('May it live Forever') is unlikely

to become 'Humanity begets waste' even in Latin 'Vastum facit

sibi' is doomed to fail. The children we all love are naturally

wasteful; we try to make them see otherwise but are poor in the

ways we relate to them. Filtering my vagueness into some sort of

positive act is quite beyond me, my work tends towards being

decorative … sans 'newspaper reading'.

It's all very difficult but we should not give up the struggle,

loving the opposition, even listening to them without despair is

frankly a bit of a nightmare. I once had a period of extreme gloom

and have been endlessly told to be more 'optoman'; the deep gloom

has left but as I have said in other places I suffer from/with a

melancholic echo. People are not schizophrenics though they might

have the schizophrenia illness and I am not gloomy even when as Mr

Churchill once said, "The Glooms are upon me". |It is unlikely we

will change our leaders to those who wish to share the joys of

life with those not in their group and as long as we clap and

cheer the rich we'll be forced collectively to share from time to

time Winston's remark of gloom.

Even after trying to absorb current news it's not possible for me

with truth to respond well to all of the current Art I see in

galleries; I feel closer to the Wilton Diptych than Damien Hirst's

multiple spot depictions but then I feel closer to A. D.

Reinhardt's 'Black' paintings than many of the Ruben's works I've

looked at … difficult, even silly to compare but I hope you catch

my drift. I still believe that our hope is in the Arts and that if

there were the sort of Christian God I don't believe in …

eternity, for me, would be in a life room learning to draw in

perfect harmony with one another, not pushing and shoving, lying

and cheating or making any attempt to be the best.

Bitten Cake

There is a lecture by Leonard Susskind where he speculates, or is

that proves, our planet to be a hologram. Mr Susskind is able to

deliver public lectures that are profound and penetrating; I like

to watch him in action even though I am unable to completely

'understand'. Why bother if you don't 'understand' a friend

recently commented which led me to thinking what exactly I

understood about understanding. As I tried to pin down my thoughts

I got more and more hooked on the notion of what it would mean to

us all if our world turned out to be holographic; in what ways

would this change our understanding?

As well as Mr Susskind's lecture I found some thoughts by Paul

Sutter … it seems that Black Holes increase their surface area

rather than their mass as they absorb matter. Like a hologram a

surface can have more information than an interior and if you

follow the two scientist's thoughts you get to the point where our

earth becomes a hologram. Their explanations are better expressed

than mine would ever be so if you're interested …

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2DIl3Hfh9tY

https://www.space.com/39510-are-we-living-in-a-hologram.html

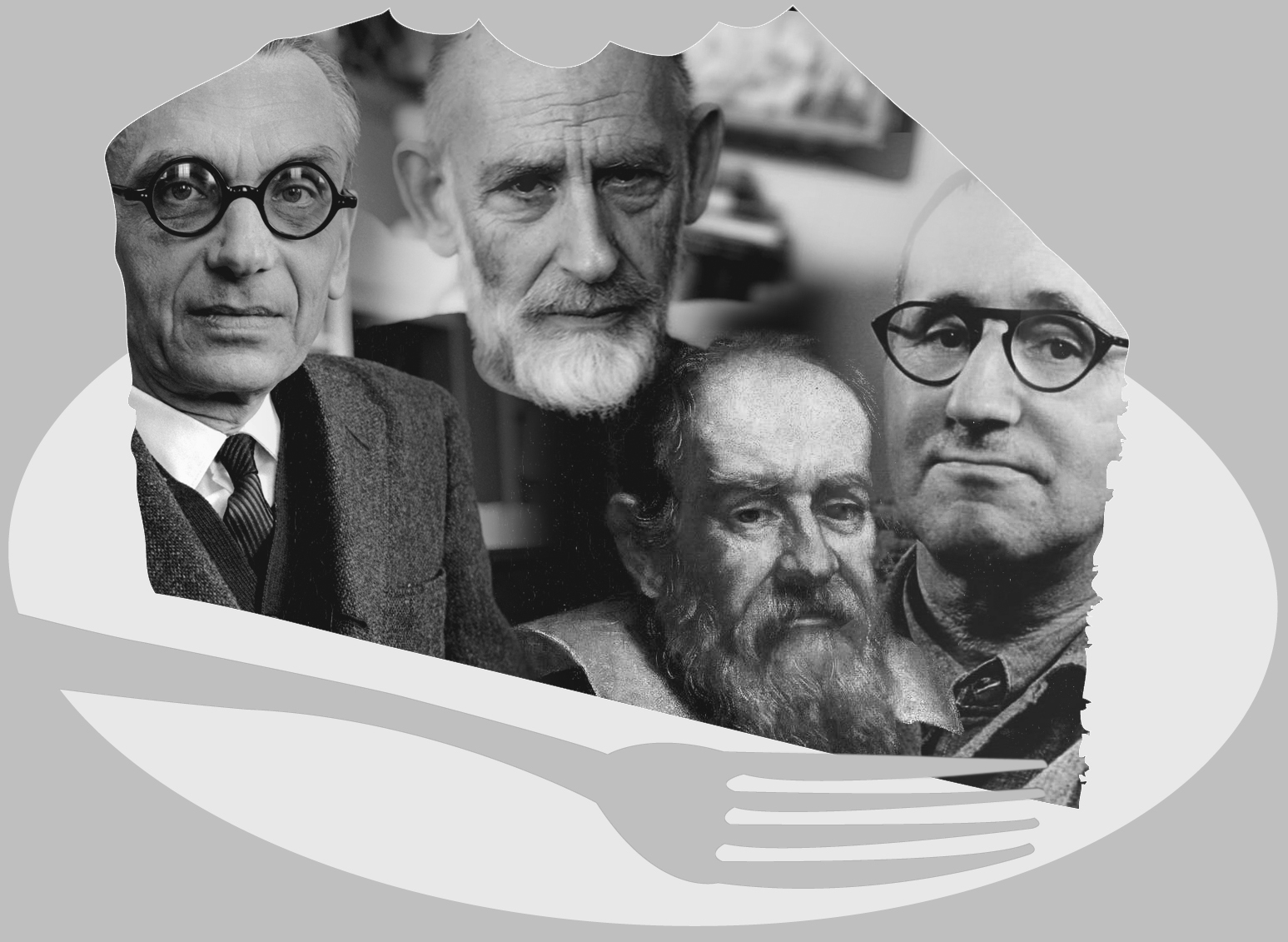

Among the names we use as signposts to thoughts in physics is

Galileo, he began to notice via both thought and experiment that

it's hard to see where a centre might be. It's interesting for me

that Art helped me learn a little of this man's struggle to

introduce new observations to others. Bertolt Brecht, in

particular in his play Galileo Galilei, brought attention of many

things to think about, one of which was the significance of

movement. Understanding, there it is again, that the Earth is

moving at high speeds has little effect on our perception of being

at rest; so, understanding is different from perception umm.

I wonder if understanding means being able to write all the things

down in logical order? However, to my mind this removes the dreamy

aspect that comes with having the thoughts floating around one's

head. Both of these aspects seem valid for me in that there are

times when we need not only to be linear but also to hold onto the

possibility of tangential thoughts adding an unexpected value.

If I try to imagine the loci my life has travelled I cannot, even

so it's fascinating to dream 'not for a single second ever in the

same place'. Pause and respond to the feeling of stillness that is

not so; imagine the different ways we are moving; rotation round

the sun, rotation round the galaxy, our daily spin and the

expansion of the universe all with no sensation of it …

breath-taking.

I have spent a large part of my life trying to think visually

about what things look like and speculate that perhaps paintings

and visual Art has got to the point where we would benefit from

Gödel's incompleteness rather than fashion. Perhaps like knowing

we are moving without the sensation of it, we live in holographic

flatness and 'dream' our three dimensional sensations as reality.

Holographic reality could become a new wonder that adds

incompleteness to my world of looking; if Art was completed we

would not need any more but I for one cannot stop myself from

wanting to work. I am unimportant, I don't know but suspect that I

am average, yet I still sit for hours attempting to make a work

that's going to deeply touch other people. Understanding what Art

is, is almost certainly better off without 'proof and truth' so

perhaps the Gödel notion is another of my Art red herrings.

It seems to me that not understanding art is as important to me as

the times when transfixed by it I feel content. We are all content

to use things without 'understanding' how they operate; for me a

favourite one is that the structure of a cake is made by egg

white. I prefer not to go into this and try to find out more about

proteins, starch et al. As with most people I just like cake and

feel no need to understand it but don't mind others doing just

that.

When entering an Art exhibition we may well be asked, "Would we

like a headphone set to hear a commentary", I have always refused.

I'm vain and almost certainly an Art snob so why would I want to

hear a verbal description, I prefer to look in silence.

As with Gödel the notion that the Earth is a hologram is a

conjecture I cannot as yet complete, perhaps completion is

understanding but I doubt it; I'm in the league of thinking that

doubts. There must have been lots and lots of Art that was made

and never seen but then I have this crazy notion that unless it is

seen Art doesn't happen or exist even. Like the old 'does a tree

falling in the forest make a sound?' I believe Art doesn't exist

unless it is looked at; then, if lucky, some of it actually

travels from the work into the looker. In a similar way that I

like cake I like Art and science and sometimes even other people I

thoroughly disagree with and don't understand.

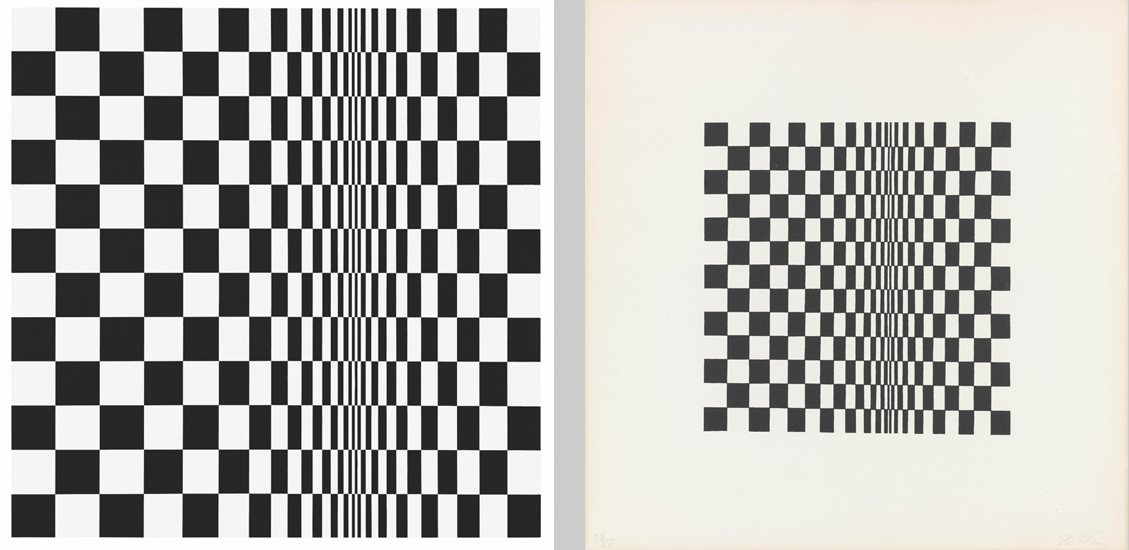

Bridgit Riley and John Foker

Years ago at West Surrey College of Art (WSCAD) I taught drawing and wish I had kept a better record of those times. As with the years I was a student there were a range of young people from various backgrounds, many of whom I imagine had been told at one time or another 'You're good at art'. Some, perhaps many of us, who have been lucky enough to have been to art school will have in a drawer or folder a few works we made from that time. What happens to us all after the student years I wonder and again wish I had kept at least the 'names and face sheets' of the students I tried to nudge towards deeper looking.

At the Mall Gallery in London there is an annual exhibition with works from members of the Society of Wildlife Artists, one is John Foker who was a student at WSCAD when I taught there. As I've said I haven't had much contact with students from back then but recently John wrote to me having come across my web site. I was, no am, delighted to have heard from him. We have exchanged a few mails and I was interested to see his work, for real rather than on a screen, though sadly I did not meet him in person.

Such a strange feeling came over me as I walked round looking at the paintings; firstly I had no idea that there was such a group and I had to think hard about how to respond. What I did first, I think naturally, was to find John's work by reading, then took off that pair of specs and had a proper look and think about all the work. I was though taken up almost entirely by the thought that John had been in a room with me some forty years ago and now here I was seeing where he'd got to. There's a café in the gallery so I bought a coffee and sat and mused about my thoughts and feelings.

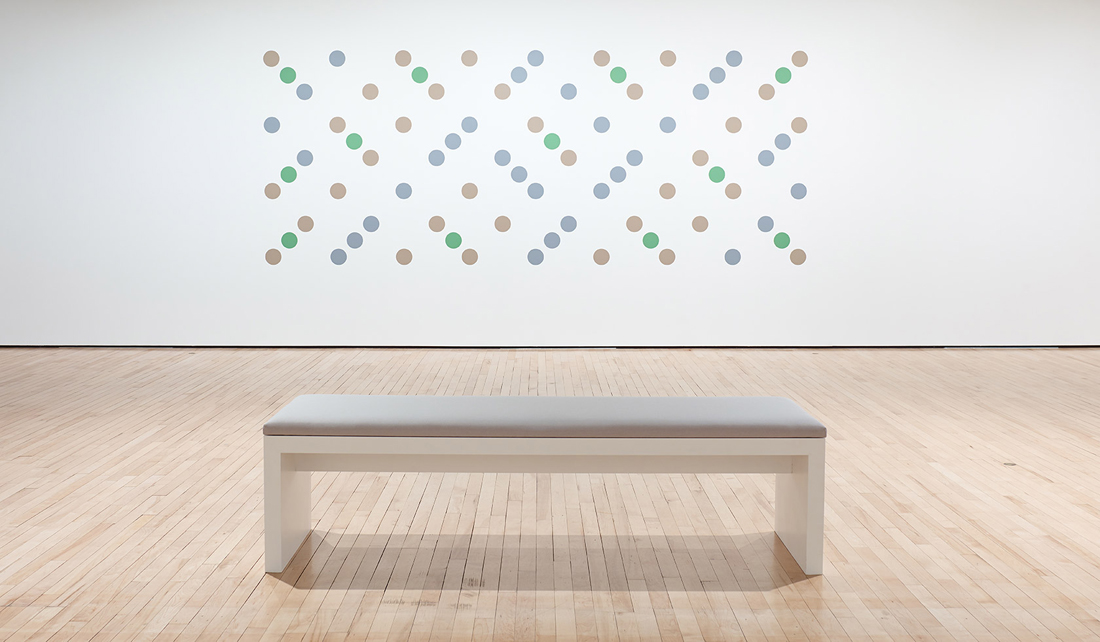

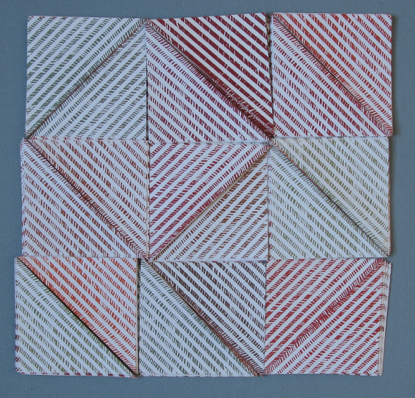

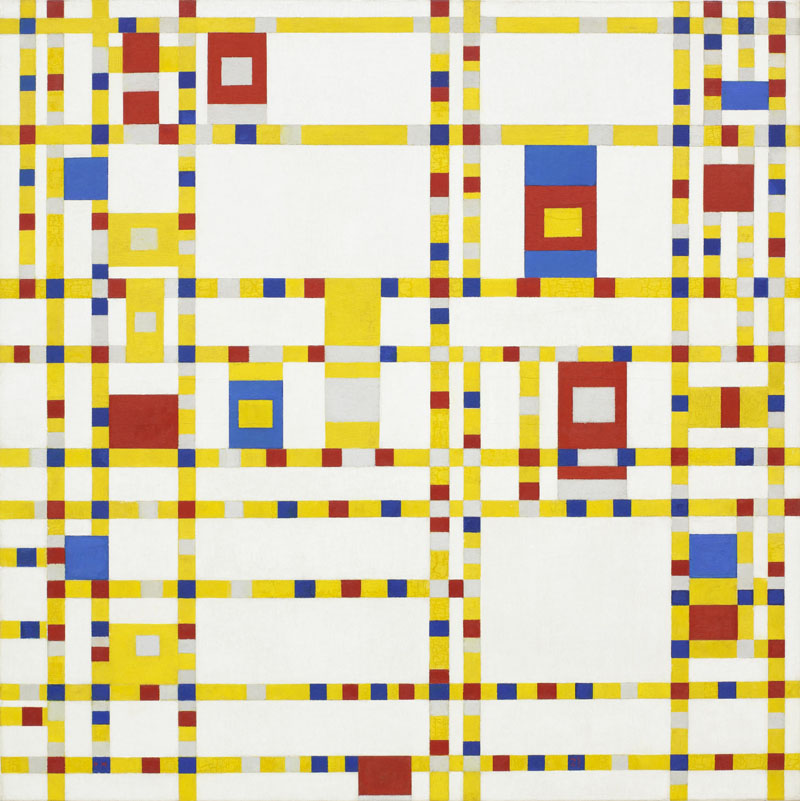

The philosopher Derrida has a poke around the word 'parergon'; now I am aware he is both liked and disliked but this 'little extra'??? romps around my thinking to this day. Painting is so very different from drawing I sometimes wonder about the leaps we have to make from one to the other. Looking at the landscape on a walk recently I wondered 'which to do? which to do? paint or draw paint or draw?' … they are so very different …yet where the picture ends belongs to both. In this Mall Gallery exhibition I could see what I would get onto again when I crossed the river and looked at the paintings of Bridgit Riley.

I went to meet Ms Riley when I was a student; this is how it happened.

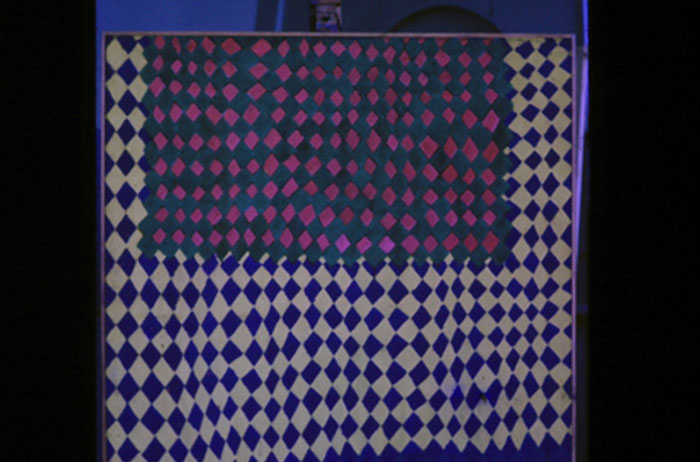

As a student apart from the excellent teaching staff there were other artists I longed to meet; I foolishly dreamt I might one day soon join 'the well known'. Among 'the names' emerging in the 1960s was Bridgit Riley, I wrote to her and asked if she'd let a few of us Students from Camberwell visit her studio in West London, she kindly agreed. What a great experience it was. I can remember her new table she was greatly pleased with that had an adjustable height. On this she had the way she worked laid out for us; there were both drawings and diagrams all routes towards her paintings. It was a gripping experience; she was open and spoke freely about the processes she worked through towards a work worth having painted. Like Donald Judd, another brilliant artist, she worked with visual thoughts in time that could be made outside of it, quite, quite wonderful. How I wish I had understood it a little better back then.

Now filled with thoughts of 'parergon' from the Mall Gallery while walking across the Thames towards the Haywood Gallery where I am thrilled to see some of Ms Riley's works. In the gallery now I can enter her work, stand and stare, trying to see her working towards this depiction. The whole concept of 'parergon' is here with some stretcher works, others directly painted onto the wall sans edge. There are many art critiques[critics'] writings about these paintings to which I can add very little in what I think of as 'In the Manner'.

I have no idea where one would learn to be an art critic and write articles 'In the Manner' some of which are deeply helpful to 'apprentice lookers'. When I was a student there were a number of watchwords; one of which was decorative, to be avoided at all costs. Some essays though describe what a looker can easily see and I think we need a range of thoughts deeper than decoration when faced with complexity.

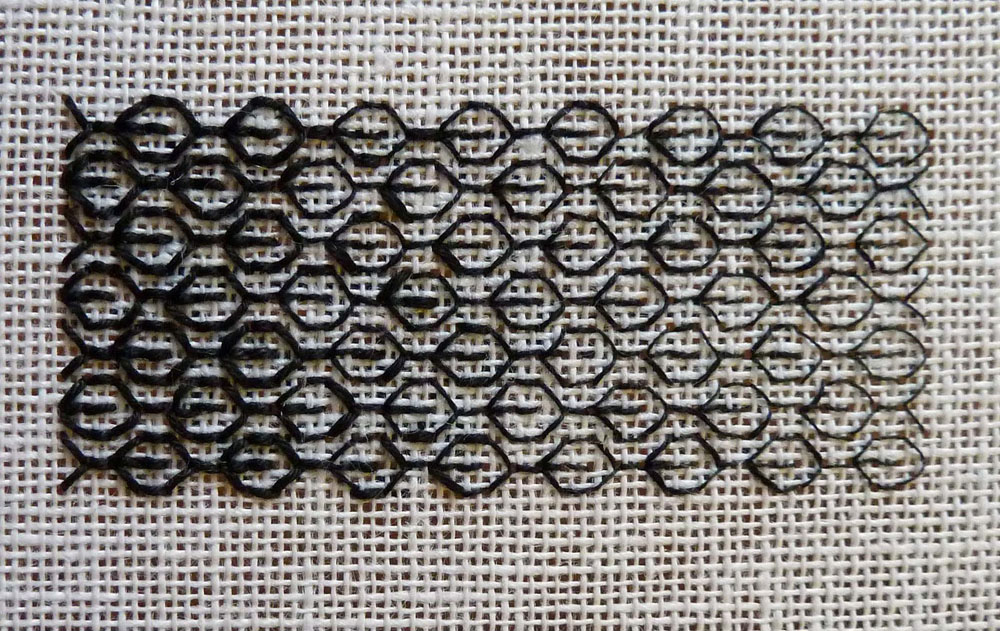

There is a limit to the number of repeats that can be made in patterns and it's interesting to have a look and think about the Penrose Pavement in Oxford. There are so many enjoyed, perhaps loved, works that are decorative. Art though is different and it's all a bit confusing. Brigit Riley knows which are which … tucked away on the top floor there are some works from her past revealing her first steps towards her humanity loving work. On 'the student visit' she took out from her rack a response to a work by Seurat I remember she passed it to me to lay on the table … now I'm in front of it hanging in the Haywood …

what a day, what a day. She looks with us

students at her 'Seurat' "I think I got the size of his/my units

wrong".

I wonder what memory really is as I stare with real joy at her

paintings …

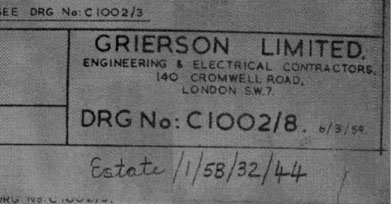

I'd had a second brush with Ms Riley, I expect she knows nothing of it but Peter Sedgley might, he dealt with me quite often. In the 1960s they opened St Catharine's Docks by Tower Bridge to artists and both had studios there. Having been an electrical engineer I got a free studio in return for getting the wiring sorted out for the artists. Hanging florescent lights in her workroom I saw again her drawings and diagrams but this time I wasn't a student and we didn't speak.

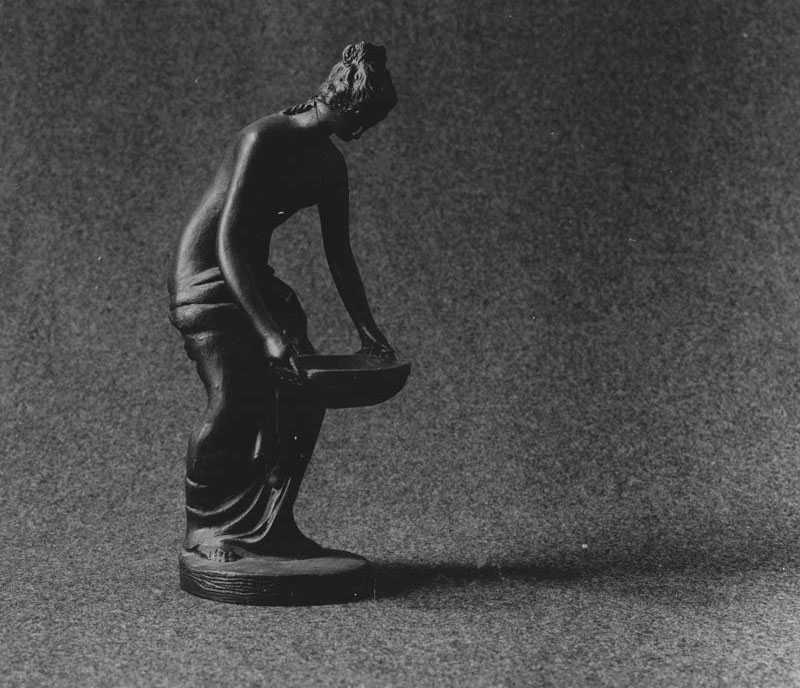

As a student, and hopefully as a teacher, finding

the 'activated space' begins before you start to draw with your

pencil or paint with your brush. Sculptures and murals differ

because their edge is even more amorphous; after being a student I

encountered an installation and thought about 'the edge' but

there's so much one'll just never fathom.

What I feel most sure of is that the 'wow' we feel is not the

image alone but the context, composition, edge, parergen perhaps.

One day in the Italian city Padua I came up against 'a wow'

without an edge, part of the mural in the Ducal Palace's bridal

chamber painted by Andrea Mantegna; even so I hang onto the need

to feel the composition as well as work it out traditionally

… learning to be content without knowing what's ideal possibly

comes with ageing.

On my journey home I mused over my life spent looking, how lucky I

have been to have seen things. John Foker took me way back to the

few years I taught art students and hope I did manage to nudge

some of us/them into a world filled with trying to discover what

the world looks like. What a wonderful day I had.

[N.B. Parergon

I only came across this word via reading and listening to talks

about the controversial Jacques Derrida. I couldn't find the word

in the Oxford Shorter Dictionary but it is described on the

Internet:

Parergon

noun

1. FORMAL

a piece of work that is supplementary to or a by-product of a

larger work.

"the second sonata is a parergon to the opera"

o ARCHAIC

work that is subsidiary to one's ordinary employment.

"he pursued astronomy as a parergon" ]

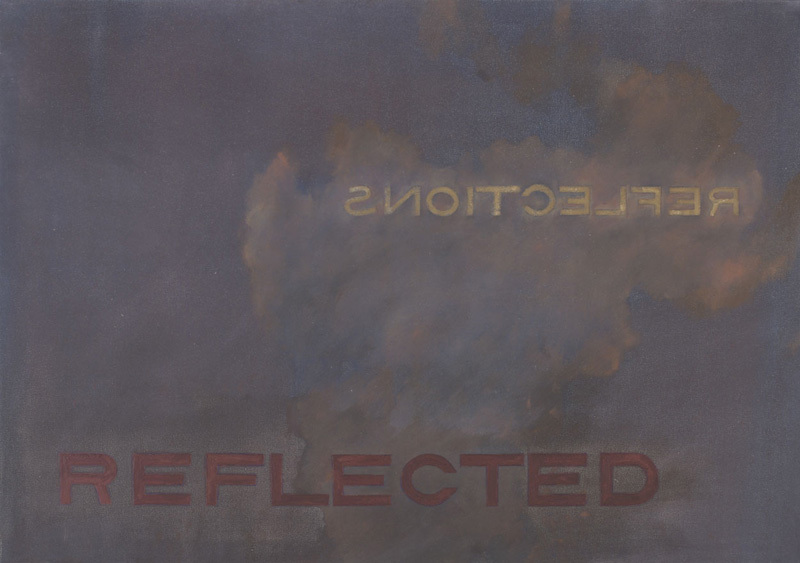

Prints on fire

Among some photographs discovered 'in my loft' were these two.

… probably taken in the late sixties when I lived in Camberwell and rented a flat in 'The Grove'; what ever was going on back then will always remain a bit of a mystery. I was heading towards what I might as well refer to as my gap years, not that I stopped working but rather that a form of vagueness descended upon me. Like many others at one time or another in our lives we face a nebulas selection from the world around us. Looking back I am so grateful that though more than a little wobbly I was able to keep some of my attention on an endless attempt to discover art. From that time there are works on plastic, a few drawings, some stacks of prints and other stuff, all-pretty much of the time.

![]()

When these print stacks resurfaced I was baffled; what ever was I up to back then? Lots of the work was easy to see as 'fashion imitation' but these … umm. I remember I had shown some in a gallery near Earlham Street but it's all very vague.

A while ago I had the prints but not the 'Loft snaps' from my time at 171A, Camberwell Grove. Many years later, now in Dorset, I hung up a couple of selections and eventually this, which I think is interesting as a work in its own right.

Burning the Periodic Table …

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HKDfEGkwT_E

… was a special event for me and even though hardly anyone has

seen the video it's not that bad a work; certainly there is the

potential there for a better one. What it needs is a rethink, a

re-film and a better ending. My plan was to put the ashes from the

burning into a cube I had sunk into the ground; the sides were

lined with mirrors and should have given the appearance of the ash

spreading out under the Earth's surface but, alas, another

failure.

---------------------------umm

The changes in what we see presented by artists has had many twists and turns since I kicked off a life spent looking. Possibly the most fundamental change is that from figurative painting and drawing through to the idea of what looking might be ('funny stuff'). This might have, no almost certainly has, led to my being somewhat discursive; not so much from subject to subject but more doubt to doubt. Things are better these days because my nervousness of getting a work visually correct doesn't have an effect on anyone but me, well none that I know of. What I have never shaken off entirely as the years roll past is my vanity, how I wish I had.

In 'A la recherché du temps perdu' Vinteuil puts

out a score he has written for visitors to notice but then

declares, "I don't know who could have put that there". Vanity

might well lead to many of us indulging in similar acts; I'm vain

in so many ways. One of the vanities of the rich promotes a

temptation of wealth among many artists. It may well be

irresistible to accept large sums of money for your work but it

also bears the burden of making obscure work for a tiny number of

people. This could boomerang to accessible works but I doubt it,

more likely to copycat works that, ideas based, are imitation

rather than the thing in itself.

Among all the current trends there are works that are difficult to

relate to because art isn't only there to comfort. As ever I am

uncertain and stuck somewhere between works that promote our

deepest thinking and the lingering memories of what I was first

taught in art school. 'Good' artists desire wholesome sharing and

our brains have to grow with newly introduced visual work as they

do with music; think of 'The Rite Of Spring' now much loved but

originally booed.

We all have responsibilities, artists have a

responsibility to balance the things around us; to help us all try

at the very least to give up the things that bring torment. Even

though it may lift our spirits for a while it's not just there to

entertain; one aim might well be for us to see a route towards an

understanding of oppositions. This seems to me to be excellent for

not just current but rather all times; it's all too easy to stamp

your foot with personal desire. I do not mean this as literal

truth, that when you look at a work you should leave with a

sentence in your mind but rather an image of things incomplete

rather than unfinished.

It's no wonder that art is difficult with so many things to dwell

upon. All those years ago as I learned to draw reality was

altered; I began a tentative understanding of the culture. Though

not educated academically enough to fully engage or understand

that culture, I cared with my desire for 'a good drawing'. This

may seem limp or simplistic but my exit from an electrical

apprenticeship towards a kind of life I had never encountered had

taken a heavy toll from which I reeled for many years.

Being as arrogant as I was back then it didn't matter to me that I was wobbly; I wanted to make work that others would notice. My current visual responses to events around us have to face 'the blank canvas' with endless practice, my often-inadequate skill, visual intelligence and any gains from talent I might be lucky to have. I crave, along with many others, a unique presentation that I can wrap up and leave behind when I finally leave. When you die you may well leave things unfinished but you are complete; almost an opposite of my personal life desire. All this dissipation is my attempt to give an answer to the few people who have seen my 'Prints On Fire' and asked "Why?"

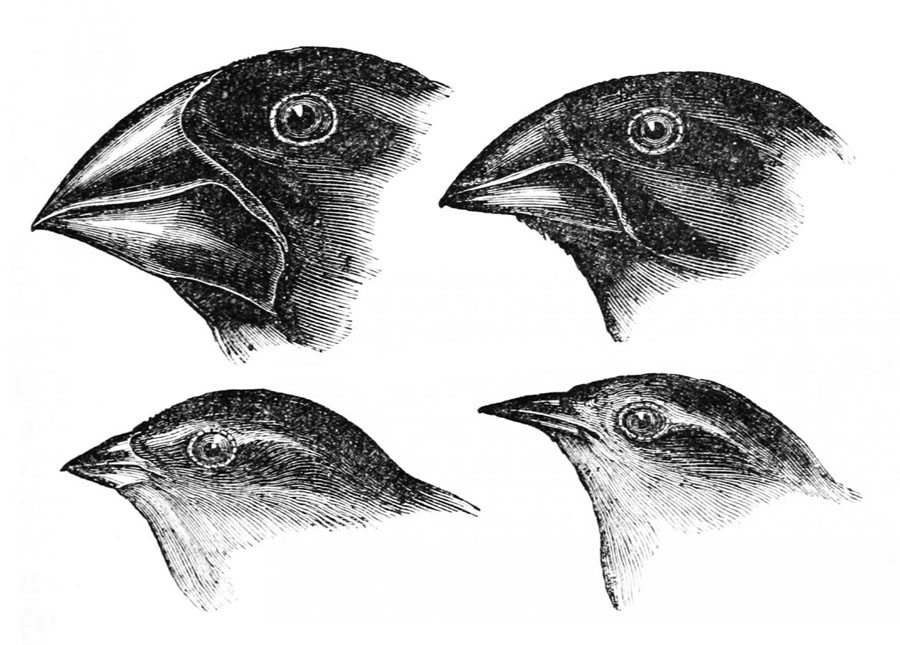

When, in my very first art school lecture, Michael Podro talked about the Parthenon my memories of 'Hero's Stories', told me by a primary school teacher Mr Williams, emerged. These were the tales that led me to the love of myths and the goddess Athena. Michael waved his arm before the screen depiction of the Marbles "Virgin, nymph and crone", he declared and his words still linger, what they mean now is different from what they meant then.

When we are engulfed with emotion and fuse it with an intellectual response we not only feel alive but also know we are. When I responded with three pictures to the Doge of Venice painted by Bellini I felt just a little closer to the wonder of art but when I burned my prints I felt a different kind of thrill.

These thoughts are certainly not content I do not fully understand them myself but I am so very glad they are there; for me to say to my self over and over "What do we mean?" is one of the wonders I have been introduced to. When I gave up one kind of life and tried out another I kept my sense of being overwhelmed hidden, at least I think that's what I was trying to do. When I set fire to my prints and watched as they burned I felt the presence of art even if I didn't really know what it was … well worth living for.

So here they are… click here for Prints on Fire: -

The Virgin print

The burning Nymph

The Crone as ash.

Teaching Art ?

In a recent edition of the R.A. magazine there are a number of interesting articles about the practice of teaching art yet not one of them says exactly what art is or even might be. This could of course be that it is too difficult or that saying what it might be merely a route towards disagreement. In the Academy's Gallery recently I overheard, "This isn't here to cheer us up." We were with the work of the artist Bill Viola, mostly projected images on video. One of his works, a triptych, shows a birth, a man afloat and a death, this was the work that prompted the remark; another work has a number of translucent screens being projected into and onto making a space to look inside as well as at. Reacting to his works varies as I wander from room to room, I walk back more than once to the 'rotating mirror room', here Mr Viola has a video presented onto a rotating screen with the mirror on the reverse side, it allows the opportunity to lean against a wall and watch as every now and then we viewers all see each other and ourselves reflected. The notion of its being easier to look at others in reflection rather than directly leads me to thoughts of us all being both together and apart. I am not content and wonder if that was Mr Viola's intention, well one of them, there are always layers of meanings to things well made.

There are also videos that freeze moments even though there is still a kind of movement or better said perhaps, an attempted 'Flow'. What I mean by 'Flow' is that wonderful connection you sometimes receive when looking deeply at visual art.

Remembering the other person's remark I too am not at all sure that these works cheer me but that doesn't mean I am not captivated by some of the thoughts shown to us. I am though somewhat confused by the inclusion in the show of drawings by Michelangelo. Apparently he saw the drawings and was moved by them then read some late texts written by the 'renaissance man'; these drawings and texts are on show alongside the video projections … umm … I think the relationship could have been better presented.

Showing a birth near a death video seems not entirely unlike an advertisement shown, also on video, at Waterloo station a few years ago. The advert's film left no doubt that "Life is Short" showing its momentary duration ending in a coffin. Of course they are very different in aim but in memory at least the sentiment that 'life is short' pokes out for us to register. Mr Viola's works are superbly filmed and keep bringing flashes from other works of art like the magic that Jean Cockteau or Robert Lepage both managed with works of film and stage both using water to transport us.

The techniques are splendid but they would not have the same memorable aspects without that seductive technology. Earth, fire, air and water are well known as the four elements of times past and Mr Viola uses them in another work that he showed in Saint Paul's Cathedral where two screen images seem to me to have worked better than the others.

Back with the thought that although we have 'Art Schools' we don't seem able to agree on what art might be. It didn't seem to matter to my generation when we were students because we mostly did painting and drawing; for many years that's what artists did but now the lure of a different kind is upon us all and I begin to feel once more like an old man lamenting.

A popular celebrity artist, I think in his Reith Lecture, paused dramatically and somewhat dismissively at the thought of Video art.

When I attempted one, a video notion of the periodic table, I also tried to link Water, Air, Fire and Earth far less dramatically than Mr Viola; I failed, mostly with the Earth part. In my notion the Table had to re-enter the Earth having been taken from Water into Air and burned. I'd dug a cube into the lawn where I was filming and lined the sides with mirror, my notion being that the ashes from 'the table' would be placed in the earth and appear to spread out beneath its surface but it didn't work at all well. Another one of my failures … but if I had enough cash I'd love to have another chance to approach correctness. As to the aspect of its 'videoness', well …umm … I think deep down I have a preference for stillness. With all the movements we now see in galleries I hang onto visual art being still; even though I am at times seduced by moving images, try them out even but … it is definitely stillness that turns my key.

Being taught to draw, taught to paint and introduced to thinking visually does not lead directly or automatically to understanding what art is or indeed the form it best dwells within. We all have to face our mistakes, to feel the joy of others' success and attempt to put the jealousy it often brings to one side; luckily self-promotion eases as the years pass.

Among all the planet dangers and fears of loss around us currently I lament our better days of visual perception and feel a different education away from academia would change many things. 'Drawing's about looking' was a chant I used when teaching small children and looking was, I hope, what we steered ourselves towards. Visual (Art) education begins with very young children and they can, if guided, begin to become visually curious; alas these days easy reproduction has brought a mist before our looking.

Dennis Healy was the only politician I know who had visual curiosity; at least I imagine so because after he died I managed to purchase a couple of his books many of which were about visual art. Mind you I don't know very much about his political views and how seeing altered his thinking but I think it must have because I am a believer in the chemical changes in our brains being as important emotionally as intellectually. Perhaps had he had more to do with education our children might rate the arts more highly and our art schools still teach students to draw.

There is a lot of confusion about looking; our head of department when I joined in the teaching of small children thought his rooms and corridors were 'highly visual'; how wrong he was! Overcrowded and en mass virtually nothing had an edge; in both senses of the word. The act of making things rather than showing them off afterwards maybe threw down an anchor for some children but I am as ever uncertain as to how much visual thinking they absorbed.